80th General Convention of The Episcopal Church: July 10 sermon by the Rt. Rev. Eugene Taylor Sutton, bishop of the Diocese of Maryland

The following is the text of a sermon recorded by the Rt. Rev. Eugene Taylor Sutton, bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Maryland, for the July 10 Sunday Eucharist of the 80th General Convention of The Episcopal Church, meeting in Baltimore through July 11.

“Tear Down the Walls”

Let us pray: Tell us what we need to hear, O God, and show us what we need to do, to be disciples of Jesus Christ. Amen.

Dear friends in Christ, we have heard in the Scripture this morning from the book of Ephesians: “For Christ is our peace; in his flesh he has made both groups into one and has broken down the dividing wall, that is, the hostility between us…thus making peace, reconciling the groups to God in one body through the cross, and thus putting to death their hostility. So he came and proclaimed peace to you who were far off and peace to those who were near” (Ephesians 2:14-17).

My friends, I want to talk with you this morning about walls. Walls. There is a memorable line from Robert Frost’s poem “Mending Wall” that goes:

Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,

That sends the frozen-ground-swell under it,

And spills the upper boulders in the sun…

There is a wall in the Holy Land that cuts through the city of Jerusalem, the city that Jesus wept for upon entering it the final days of his earthly life. Just as he did 2,000 years ago, Jesus weeps today. The wall in Israel/Palestine the government calls the “Security Fence,” but our Arab sisters and brothers refer to it as the “Wall of Separation.” It is the wall that is designed to keep people apart from each other. To keep out our Palestinian siblings from entering at will those in Israel.

Most people believe that the wall in Israel/Palestine won’t succeed in keeping people out and won’t give the Israelis the security they so desperately desire and deserve. Walls of separation simply do not work; they never have.

There is something about a wall that God does not like. Since biblical times, God keeps tearing down walls. Take, for example, the Tower of Babel in Genesis chapter 11. According to the story, the human race began with speaking one single language, and in their pride, they built a city with a walled tower meant to reach above the heavens. It was to be a monument to their uniformity and their power. But the Lord God destroyed that wall of uniformity and confounded their speech, saying, in effect, “No, it is not my vision that you will all be the same. My vision is that you will celebrate diversity—not uniformity—and that you will find a way to communicate across many tongues and cultures, and live as one humanity based on love, not sameness.” That tower of conformity had to come down.

And do you remember in the book of Joshua, chapter 6, the story of the walls of Jericho? Those walls had been built by the Canaanites to keep the people of God out of that city. But you can’t keep God’s people out by a mere wall. The Lord God commanded Joshua’s army to march around that city 13 times in seven days, and then blow their trumpets. I imagine they were like the Baptist church choir that I grew up in; that choir of my upbringing could sing so loud and exuberantly that they could blow the roof off any structure and its walls. Joshua’s army of choristers blew that wall down.

There was Hadrian’s Wall, built in the second century by the Roman Emperor Hadrian to keep out the barbarians to the north. Even though the wall stretched completely across the 73-mile width of Northern England, it ultimately failed to keep out the tribes migrating south of that border. Tourists and locals still walk all over that wall today.

There’s the Great Wall of China, begun seven centuries before Christ and improved greatly during the Ming Dynasty in the 17th century to also keep out invaders from various nomadic groups from Eurasia. Yet, today, thousands of invaders from the East and West arrive there every year in tour buses to gaze at and sometimes hike sections of that wall. That wall doesn’t keep out anybody.

And there’s hardly a serious student of history and demographic movements of people who believe that a wall stretching out along the southern border of the United States will keep people out who are desperately poor and terrorized in the countries of their birth, and who believe that if only they can get into this land of freedom and promise, maybe by hard work and good luck, they can live and feed their families. A mere wall will not deter them. Walls never do.

These physical walls are but visible manifestations of another wall, an “invisible” one, that is much more insidious and dangerous. It is the systemic, economic, and racial wall of separation between peoples.

Such is the wall in this city of Baltimore, a wall that cuts through this metropolis like a knife. At first glance you cannot see it, but it doesn’t take long for a resident to feel its reality. It is the very real wall between rich and poor, Black, Brown, and White, the highly educated and the poorly educated, the haves and the have-nots, the upwardly mobile and the left behind.

These are the same “walls” all over the richest nation on earth, walls of persistent injustice, hatred, and bigotry. Just as in Jerusalem 2,000 years ago, Jesus weeps over this city today, because he loves it so much.

On June 12, 1987, at the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin, Germany, President Ronald Reagan said in a famous speech: “MR. GORBACHEV, TEAR DOWN THIS WALL!” And within a few years, that wall of totalitarian states all over Europe came a-tumblin’ down.

I believe God is telling us today, “Episcopal Church, tear down those walls! Tear down the walls of separation in your church, in your nations, in your cities, in your societies.” But how? How do we do that?

Well, first of all, we’re going to have to have some humility before we start tearing stuff down and trying to save the world on our own. Here’s the thing: the world has a Savior, and we ain’t Him. There’s a reason why we worship Our Savior Jesus Christ, and not ourselves, because as good as we think we are, we’re not always as good as we say we are.

The truth is, there are a lot of things that The Episcopal Church is just not good at. God knows, as a bishop, many times I’m not that good at that. I get it wrong at least as much as I get it right. And that’s true of my beloved diocese as well. Maryland is just not that good at a lot of things. I want you to know that in my first years here, I was a kind of “cocky” bishop, thinking that I could just change things—maybe that’s what all new bishops think, that they alone can lead everybody into change. I wanted to lead this diocese onto a path of unprecedented growth, evangelism, stewardship, and Christian formation. We were going to protect our land and waters here in Maryland from environmental degradation, and we were going to be at the forefront of combating gun violence and diminishing poverty. And oh, did I forget to tell you: We were going to change the world! We even came up with numerical goals of growth in a big campaign called Horizons 2015.

Well, on paper, we didn’t make any of those goals. We failed. But there’s one thing that we here in Maryland have worked our tails off in trying to do, and we’re getting really good at it: love. We love; we talk openly about love, we practice it, and when we fail to love right, then we call each other out on it. We work at it; we work at loving God with all our heart, soul, mind, and strength; we really work on loving our neighbors as ourselves. To us, doing justice is just love in action on a social scale, and so we especially work at loving the poor, the outcast, the downtrodden, and the disinherited. We’ve been trying to zero in on what the presiding bishop has been preaching for years—that if we don’t get love right, then we don’t get anything right! All the evangelism efforts, new church starts, and church revitalization efforts don’t mean a darn thing if we don’t get love right.

We are a community of love; that’s our vision statement. Years from now the world at large probably won’t know a whole lot about The Episcopal Church in these parts, but they will know this: That “those Episcopalians—they really know how to love each other, and everybody.”

And that my friends, is why we’ve doubled down here on racial reconciliation in Maryland. It’s because of love. That is why we are committed to reparations. If you’re going to tear down walls of centuries of injustice, then you’re going to have to get serious about repairing the damage that still persists today as a direct result of the past. Reparations is whatever someone or some institution does to repair something that’s broken. It has its roots in the Old Testament, in Isaiah 58:3-12:

“Why do we fast, but you do not see? Why humble ourselves, but you do not notice? Look, you serve your own interest on your fast day, and oppress all your workers… Is such the fast that I choose, a day to humble oneself?..to loose the bonds of injustice, to undo the thongs of the yoke, to let the oppressed go free, and to break every yoke? Is it not to share your bread with the hungry, and bring the homeless poor into your house; when you see the naked, to cover them, and not to hide yourself from your own kin? Then your light shall break forth like the dawn, and your healing shall spring up quickly…Your ancient ruins shall be rebuilt; you shall raise up the foundations of many generations; you shall be called the repairer of the breach, the restorer of streets to live in.”

That, my friends, is the work of reparations, which simply means to repair the breach, to repair the brokenness that we see about us. It is a profound act of reconciliation: the act of putting back together the broken pieces that prevent wholeness—it’s a restoring of community and harmony. In May of 2019 at our annual convention, the Diocese of Maryland took a bold step toward reconciliation. It voted unanimously to affirm my pastoral letter on racial reconciliation that called for this diocese to commit itself to reparations as one of the means of reckoning with our collusion with and participation in.the enslavement of peoples on our soil, and the hundred-plus years of slavery and racial discrimination after it.

Why? Why did our 90% White diocese, stretching from Appalachia to the Chesapeake Bay, Republican and Democrat, urban and rural, rich and poor, conservative and progressive, why did we vote to take monies out of our financial resources and return it—that’s right, not “give it,” but “return it”—to impoverished Black communities across the state? Because we wanted to follow Jesus, and we asked ourselves, “What would Jesus do?” If Jesus were speaking to our diocese today, having enriched itself in no small part on the backs of Black and Brown bodies and did not compensate them for centuries of their labor, what would he have us do? Just say that was then, this is now, bad stuff happens, it wasn’t all that bad, we’re all one now, let’s just sing “Kum Ba Yah” and say that we’re reconciled? What would Jesus want us to do – not “feel,” not “wish for,” but “do?”

We discerned that Jesus first wanted us to tell the truth about ourselves. And the truth is, The Episcopal Church stole. We stole Black lives, and from Black livelihoods. We destroyed their families. We dehumanized them, degraded them, treated them like dirt, and legislated for hundreds of years that they were not fully “persons.” And then after 250 years of enslaving them—yes, we did, in The Episcopal Church and their clergy—we, for most of the years since slavery, profited from social and economic structures that made sure that Black people would be treated as inferior citizens to White people, making it much more difficult to own property, to vote (and that’s still going on now, people, trying to suppress that vote), and tried our best to make sure that Black people would not get a good education, would not get good jobs, would not get good health care, would not make money—resulting in generations of communities that could not hand down wealth to its descendants. These are the disinherited that Howard Thurman talked about in his famous book, “Jesus and the Disinherited.” Our nation ended slavery in 1865 after a bloody civil war waged to protect that evil institution, but we gave no property or monies to formerly enslaved persons for their centuries of uncompensated labor.

What would Jesus do? Well, we know what Jesus’ followers did. The Episcopal Church in the South helped to shape Jim Crow segregation, and the whole church was largely silent for at least a century about racial segregation, lynchings, redlining, voter suppression, unfair employment practices, and other forms of racial injustice.

But for the last 20 years or so, beginning during the episcopate of my predecessor and present colleague as my assistant bishop, Bishop Bob Ihloff, and our former Suffragan Bishop John Rabb, we uncovered our history in order to get at the truth. We fearlessly looked at our diocesan history and told the story; and we encouraged our parishes to uncover their histories and tell their stories of how they related to the Black community. And you know, sometimes the truth hurts—but we heard Jesus say, “It will also set you free.” Tell the truth!

What would Jesus do? What is he telling us? We learned something in Sunday School a long time ago: If you steal something from someone, you pay it back. And if you can’t pay it all back, you take steps to make amends. When we began to show how much this White church gained from centuries of racial injustice, that just didn’t sit well with us. That stuck in our craw. We kept hearing Jesus say, “Pay down the debt you owe to the impoverished Black communities in this state.”

So, at the next diocesan convention we voted overwhelmingly to start a seed fund of $1 million. That figure was not a mathematical computation, but a moral one. It’s taken from endowments and other diocesan funds and represents about 20% of our annual budget. It’s going to put a dent in some other things we want to do; it will hurt, and it should. Because it’s owed, it’s owed the Black community. After centuries of stealing money from the African American community, we’re going to invest in the impoverished Black community. We’re funding projects in education, housing, health care, the environment, and economic development to repay some of that debt.

The response of the wider community has been overwhelmingly positive, frankly, much to my surprise. I expected more resistance. But we’re still receiving letters and checks from individuals throughout Maryland who say, “Thank you, Diocese of Maryland, you’ve finally admitted the truth, and you’re putting your money where your mouth is. Enclosed is a check; I want to help.” One such gift came unexpectedly from a very small congregation in a coal mining town, St. James Church in Westernport. Their ancestors had nothing to do with slavery, but they wanted to be in solidarity with uplifting underinvested and impoverished Black communities especially in the western rural parts of our diocese. When I visited them last year, they presented me with a check for $10,000. That small, mostly rural, White congregation. That’s what love does, and they got it.

You know, all too often we want to do reconciliation on the cheap. We don’t want to pay the price of being reconciled; we want it for free; we want it to be easy and all smiles. But if reconciliation doesn’t cost anything, then it’s not worth anything! There is no reconciliation without a reckoning, and the time is now. If you don’t think the time is now, tell me when; give me a date—when is the time for justice? We believe it’s now. The payment of reparations is a reckoning for the racial sins of our nation and our church against persons with beautiful Black skin like mine.

And friends, don’t let retrograde voices and forces against this reckoning poison your minds and scare you about what reparations supposedly means. Reparations is not White people writing checks to Black people. No, it’s about what this generation will do to correct an injustice that previous generations failed to do. They lacked the courage to repay formerly enslaved persons; they kicked that can down the road. But the can is still on the road; it didn’t go anywhere. Will this generation show enough courage and faith, and love to do the right thing after so many years of saying, “It just can’t be done,” or “Reparations will never fly in this country”? Well, maybe for some folks, but not for Black folks.

There is such a thing as a “collective culpability.” The Diocese of Maryland’s experience with communities of African descent is different from Hawaii’s, or Arizona, Minnesota, Taiwan, Central America, or Puerto Rico. The response of every diocese to racism is going to be different due to different histories and contexts. But we all live in a world where darker-skinned people are treated as “less than” in relation to lighter-skinned people: all over the world.

And all of us belong to this church, which has collectively benefitted financially from slavery and racial segregation. We know, or should know, the history of how our church received substantial portions of its financial resources from racist sources. We know the truth about how the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel (SPG) derived much of its income from sugar plantations that made use of slave labor, and we know that two of the founders of the Domestic & Foreign Missionary Society (DFMS) also founded the American Colonization Society—of which Francis Scott Key, the author of “The Star-Spangled Banner” and a vestryman at All Saints Church in Frederick, was a prominent proponent of its aims to deport freed slaved people in this country—to deport them. We have all benefitted financially from institutionalized racism.

Some dioceses and institutions have already begun to address the reckoning; Maryland is not the only one. There are several other dioceses that have already made commitments to reparations or who are at some stage of educating themselves; you know who you are, and I want to say THANK YOU; Maryland thanks you. In addition to these and other diocesan efforts, this convention will vote on a resolution from the Presiding Officers’ Working Group on Truth-telling, Reckoning, and Healing that calls for the establishment of an Episcopal Coalition for Racial Equity and Justice as a voluntary association of Episcopal dioceses, parishes, organizations, and individuals. Folks, it’s these kinds of bold proposals that will move our church forward toward racial justice for many years to come, and I hope you will support them.

It’s going to take all of us to fix this. It doesn’t matter if your ancestors came over on these shores on the Mayflower or on a slave ship; it doesn’t matter if they owned slaves or were themselves enslaved, it doesn’t matter if you’re a Northern diocese or a Southern diocese, or if you’re in Europe or Asia or Central America; it doesn’t matter if you’re a recent immigrant or one whose family has been here for generations—we’re all in the same boat now. I am committed to being a part of the solution; I’m paying into our diocesan Reparations Fund, even though my country and my own church enslaved my people. Your protestations that you aren’t racist and had nothing to do with the fact that millions of African Americans are entrapped in systemic poverty, that will hold no water with me. We’ve all inherited a racial mess; we swim in an ocean of racism in this country, and fish don’t know they’re wet. We didn’t cause it, but we have to fix it. Reparations is not about guilt; it’s about responsibility. We all have a responsibility to repair the damage of centuries of theft.

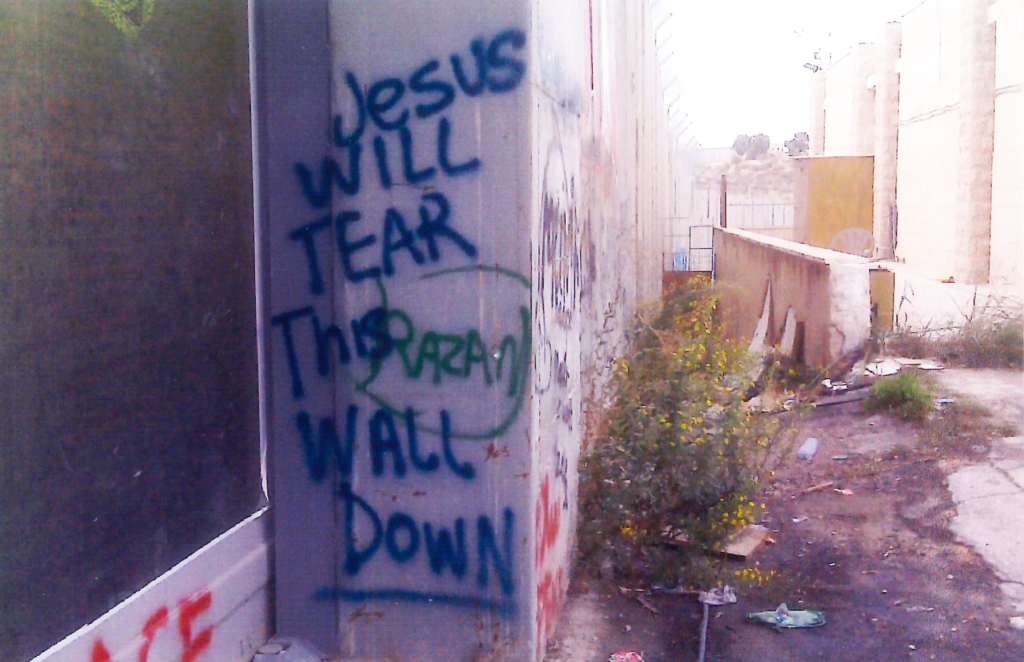

I want to leave you with a photo that was taken when I made my first pilgrimage to the Holy Land from this diocese in 2008. It’s a photo of a section of the wall in Jerusalem, that separation wall, where someone spray-painted these words: JESUS WILL TEAR DOWN THIS WALL! And so he will. That wall’s going to go; they all do. Our Lord is inviting us to join him in this work. So, friends, let’s roll up our sleeves. Let’s rebuild our communities with the resources we have. Let’s make great strides to tear down all walls of inequity and injustice and start building bridges across the divides in our communities, in our churches, in our dioceses, and across The Episcopal Church. And as we do so, may we give all honor and glory to God, now and forever. Amen.

80ª Convención General de la Iglesia Episcopal Sermón del 10 de julio por el Reverendísimo Eugene Taylor Sutton, obispo de la Diócesis de Maryland

El siguiente es el texto de un sermón grabado por el Reverendísimo Eugene Taylor Sutton, Obispo de la Diócesis Episcopal de Maryland, para la Eucaristía Dominical del 10 de julio de la 80ª Convención General de la Iglesia Episcopal, que se reúne en Baltimore hasta el 11 de julio.

“Derrota las paredes”

Oremos: Díganos lo que necesitamos oír, oh, Dios, y muéstranos lo que necesitamos hacer, para ser discípulos de Jesucristo. Amén.

Queridos amigos en Cristo, hemos escuchado en la Escritura esta mañana del libro de Efesios: “Porque él es nuestra paz, que de ambos pueblos hizo uno, derribando la pared intermedia de separación, aboliendo en su carne las enemistades, la ley de los mandamientos expresados en ordenanzas, para crear en sí mismo de los dos un solo y nuevo hombre, haciendo la paz, y mediante la cruz reconciliar con Dios a ambos en un solo cuerpo, matando en ella las enemistades. Y vino y anunció las buenas nuevas de paz a vosotros que estabais lejos, y a los que estaban cerca” (Efesios 2:14-17).

Mis amigos, quiero hablar con ustedes esta mañana sobre lo muros. Muros. Hay un verso memorable del poema de Robert Frost “Mending Wall” (Reparando el Muro) que dice:

Hay algo que no ama un muro,

Que envía el oleaje de la tierra congelada debajo de él,

Y arroja las rocas superiores al sol…

Hay un muro en Tierra Santa que atraviesa la ciudad de Jerusalén, la ciudad por la que Jesús lloró al entrar en ella los últimos días de su vida terrenal. Así como lo hizo hace 2.000 años, Jesús llora hoy. El muro en Israel/Palestina el gobierno llama la “Valla de Seguridad”, pero nuestros hermanos y hermanas árabes se refieren a ella como el “Muro de la Separación”. Es el muro que está diseñado para mantener a las personas separadas entre sí. Para evitar que nuestros hermanos Palestinos entren a voluntad para acceder a aquellos que están en Israel.

La mayoría de la gente cree que el muro en Israel/Palestina no logrará mantener a la gente fuera y no le dará a los israelíes la seguridad que tanto desean y merecen. Los muros de separación simplemente no funcionan; nunca lo han logrado.

Hay algo acerca de un muro que a Dios no le gusta. Desde los tiempos bíblicos, Dios sigue derribando muros. Tomemos, por ejemplo, la Torre de Babel en Génesis capítulo 11. Según la historia, la raza humana comenzó hablando un solo idioma, y en su orgullo, construyeron una ciudad con una torre amurallada destinada a alcanzar los cielos. Iba a ser un monumento a su uniformidad y su poder. Pero el Señor Dios destruyó ese muro de uniformidad y condenó su discurso, diciendo, en efecto, “No, no es mi visión que todos ustedes sean iguales. Mi visión es que celebréis la diversidad—no la uniformidad—y que encontréis una manera de comunicaros a través de muchas lenguas y culturas, y viváis como una humanidad basada en el amor, no en la igualdad”. Esa torre de conformidad tuvo que derrumbarse.

¿Recuerdan en el libro de Josué, capítulo 6, la historia de los muros de Jericó? Esos muros habían sido construidos por los Cananeos para mantener al pueblo de Dios fuera de esa ciudad. Pero no se puede mantener al pueblo de Dios afuera por un simple muro. El Señor Dios ordenó al ejército de Josué marchar alrededor de esa ciudad 13 veces en siete días, y luego hacer sonar sus trompetas. Me imagino que eran como el coro de la iglesia Bautista en el que crecí; ese coro de mi crianza podía cantar tan fuerte y exuberantemente que podían volar el techo de cualquier estructura y sus muros. El ejército de cantores de Josué derribó ese muro.

Estaba el Muro de Adriano, construido en el siglo II por el Emperador Romano Adriano para impedirle la entrada a los bárbaros al norte. A pesar de que el muro se extendía completamente a lo largo de las 73 millas de ancho del Norte de Inglaterra, finalmente no logró mantener alejadas a las tribus que emigraban al sur de esa frontera. Los turistas y los lugareños todavía recorren ese muro hoy en día.

Está la Gran Muralla de China, iniciada siete siglos antes de Cristo y mejorada grandemente durante la Dinastía Ming en el siglo 17 para también mantener alejados a los invasores de varios grupos nómadas de Eurasia. Sin embargo, hoy en día miles de invasores del Este y del Oeste llegan allí cada año en autobuses turísticos para observar y a veces caminar secciones de ese muro. Ese muro no le prohíbe la entrada a nadie.

Y apenas hay un estudiante serio de historia y movimientos demográficos de pueblos que creen que un muro que se extiende a lo largo de la frontera sur de los Estados Unidos mantendrá alejada a las personas desesperadamente pobres y aterrorizadas en los países de su nacimiento, y que creen que, si sólo pueden entrar en esta tierra de libertad y promesa, tal vez a través de trabajo duro y buena suerte, pueden vivir y alimentar a sus familias. Un simple muro no los disuadirá. Los muros nunca logran eso.

Estos muros físicos no son sino manifestaciones visibles de otro muro, uno “invisible”, que es mucho más insidioso y peligroso. Es el muro sistémico, económico y racial de separación entre las personas.

Tal es el muro en esta ciudad de Baltimore, un muro que atraviesa esta metrópolis como un cuchillo. A primera vista no se puede ver, pero no toma mucho tiempo para que un residente sienta su realidad. Es el verdadero muro entre ricos y pobres, afroamericanos, hispanos y caucásicos, los muy educados y los de bajos niveles de educación, los que tienen y los que no tienen, los socialmente desarrollados y los socialmente desatendidos.

Estos son los mismos “muros” por toda la nación más rica de la tierra, muros de persistente injusticia, odio e intolerancia. Como en Jerusalén hace 2.000 años, Jesús llora sobre esta ciudad hoy, porque la ama tanto.

El 12 de junio de 1987, en la Puerta de Brandemburgo en Berlín, Alemania, el Presidente Ronald Reagan dijo en un famoso discurso: “Sr. GORBACHOV, ¡DERRIBE ESE MURO!” Y en pocos años, ese muro de los Estados totalitarios de toda Europa se derrumbó.

Creo que Dios nos está diciendo hoy, “Iglesia Episcopal, ¡derriben esas paredes! Derriben los muros de separación en su iglesia, en sus naciones, en sus ciudades, en sus sociedades”. Pero ¿cómo? ¿Cómo lo hacemos?

Bueno, en primer lugar, tengamos un poco de humildad antes de empezar a derribar las cosas y tratar de salvar el mundo por nuestra cuenta. Aquí está el detalle: el mundo tiene un Salvador, y nosotros no somos Él. Hay una razón por la que adoramos a nuestro Salvador Jesucristo, y no a nosotros mismos, porque por muy buenos que pensemos que somos, no siempre somos tan buenos como decimos que somos.

La verdad es que hay muchas cosas en las que la Iglesia Episcopal simplemente no es tan buena. Dios sabe que, como obispo, muchas veces no soy tan bueno. Me equivoco al menos tantas veces como hago el bien. Y eso es cierto también para mi querida diócesis. Maryland no es tan buena en muchas cosas. Quiero que sepan que en mis primeros años aquí, yo era una especie de obispo “arrogante”, pensando que podría cambiar las cosas—tal vez eso es lo que piensan todos los obispos nuevos, que ellos solos pueden llevar a todos a lograr el cambio. Quería guiar a esta diócesis hacia un camino de crecimiento, evangelización, mayordomía y formación cristiana sin precedentes. Íbamos a proteger nuestra tierra y nuestras aguas aquí en Maryland de la degradación ambiental, y íbamos a estar a la vanguardia de la lucha contra la violencia armada y la disminución de la pobreza. Y oh, me olvidé de decirles: ¡Vamos a cambiar el mundo! Incluso nos encontramos con objetivos numéricos de crecimiento en una gran campaña llamada “Horizons 2015”.

Bueno, en teoría, no alcanzamos ninguna de esas metas. Fracasamos. Pero hay una cosa que nosotros aquí en Maryland nos hemos esforzado en tratar de hacer, y nos estamos volviendo realmente buenos en ello: amar. Amamos; hablamos abiertamente sobre el amor, lo practicamos, y cuando fallamos en amar bien, entonces nos reprendemos los unos a los otros. Trabajamos en ello; trabajamos en amar a Dios con todo nuestro corazón, alma, mente y fuerza; realmente trabajamos en amar a nuestros vecinos como a nosotros mismos. Para nosotros, hacer justicia es sólo amor en acción a escala social, y por eso trabajamos especialmente en amar a los pobres, a los marginados, a los oprimidos y a los desheredados. Hemos estado tratando de centrarnos en lo que el obispo primado ha estado predicando durante años—que, si no amamos bien, ¡entonces no hacemos nada bien! Todos los esfuerzos de evangelización, los cimientos de nuevas iglesias y los esfuerzos de revitalización no significan nada si no amamos bien.

Somos una comunidad de amor; esa es nuestra visión. Dentro de unos años, el mundo en general probablemente no sabrá mucho sobre la Iglesia Episcopal sobre estos temas, pero sabrán esto: Que “aquellos Episcopales—realmente saben amarse unos a otros, y a todos los demás”.

Y eso, amigos míos, es por qué hemos reiterado aquí en lo que se refiere a la reconciliación racial en Maryland. Es por amor. Por eso estamos comprometidos con las reparaciones. Si se van a derribar muros de siglos de injusticia, entonces van a tener que tomar en serio la reparación del daño que todavía persiste hoy como resultado directo del pasado. Reparaciones son lo que alguien o alguna institución hace para reparar algo que está roto. Tiene sus raíces en el Antiguo Testamento, en Isaías 58:3-12:

¿Por qué, dicen, ayunamos, y no hiciste caso; ¿humillamos nuestras almas, y no te diste por entendidos? He aquí que en el día de vuestro ayuno buscáis vuestro propio gusto, y oprimís a todos vuestros trabajadores. ¿Es tal el ayuno que yo escogí, que de día aflija al hombre su alma, que incline su cabeza como junco, y haga cama de cilicio y de ceniza? ¿Llamaréis esto ayuno, y día agradable a Jehová? ¿No es más bien el ayuno que yo escogí, desatar las ligaduras de impiedad, soltar las cargas de opresión, y dejar ir libres a los quebrantados, y que rompáis todo yugo? ¿No es que partes tu pan con el hambriento, y a los pobres errantes albergues en casa; que cuando ves al desnudo, lo cubres, ¿y no te escondas de tu hermano? entonces nacerá tu luz como el alba, y tu salvación se dejará ver pronto; e irá tu justicia delante de ti, y la gloria de Jehová tu retaguardia. Y los tuyos edificarán las ruinas antiguas; los cimientos de generación y generación levantarás, y serás llamado reparador de portillos, restaurador de calzadas para habitar”.

Esa es, amigos míos, la tarea de reparar, que simplemente significa reparar la grieta, reparar el quebrantamiento que vemos en nosotros. Es un acto profundo de reconciliación: el acto de volver a unir las piezas rotas que impiden la plenitud—es una restauración de la comunidad y la armonía. En mayo de 2019, en nuestra convención anual, la Diócesis de Maryland dio un gran paso hacia la reconciliación. Votó unánimemente a favor de afirmar mi carta pastoral sobre la reconciliación racial, que pedía a esta diócesis que se comprometiera a hacer reparaciones como uno de los medios para hacer frente a nuestra colusión y participación en la esclavitud de los pueblos de nuestro suelo, y los más de cien años de esclavitud y discriminación racial posteriores.

¿Por qué? ¿Por qué nuestra diócesis, 90% Caucásica, que se extiende desde los Apalaches hasta la Bahía de Chesapeake, Republicana y Demócrata, urbana y rural, rica y pobre, conservadora y progresista, ¿Por qué votamos para retirar dinero de nuestros recursos financieros y devolverlo—es correcto, no “darlo”, sino “devolverlo”—a las comunidades afroamericanas empobrecidas de todo el estado? Porque queríamos seguir a Jesús, y nos preguntamos: “¿Qué haría Jesús?” Si Jesús le estuviera hablando a nuestra diócesis hoy, habiéndose enriquecido a sí misma en gran parte con las espaldas de los Afrocolombianos e Hispanos y no los compensara por siglos de su trabajo, ¿qué nos haría hacer? Sólo decir que eso fue antes, esto es el ahora, cosas malas pasan, no era tan malo, todos somos uno ahora, ¿vamos a cantar “Kum Ba Yah” y decir que estamos reconciliados? ¿Qué querría Jesús que hiciéramos– no “sentir”, no “desear”, sino “hacer”?

Discernimos que Jesús primero querría que dijéramos la verdad acerca de nosotros mismos. Y la verdad es que la Iglesia Episcopal robó. Robamos vidas Afroamericanas, y de los sustentos de ellos. Destruimos a sus familias. Los deshumanizamos, los degradamos, los tratamos como suciedad y durante cientos de años legislamos que no eran plenamente “personas”. Y luego, después de 250 años de esclavizarlos—sí, lo hicimos, en la Iglesia Episcopal y su clero—durante la mayoría de los años desde la esclavitud, nos aprovechamos de las estructuras sociales y económicas que aseguraron que los Afroamericanos fueran tratados como ciudadanos inferiores a los Caucásicos, haciendo que sea mucho más difícil poseer propiedad, votar (y eso sigue ocurriendo ahora, gente, tratando de suprimir ese voto), e hicieron todo lo posible para asegurar que los Afroamericanos no obtuvieran una buena educación, no obtuvieran buenos trabajos, no recibieran una buena atención médica, no obtuvieran dinero, lo que dio lugar a generaciones de comunidades que no podían entregar capital a sus descendientes. Estos son los desheredados de los que hablaba Howard Thurman en su famoso libro “Jesús y los Desheredados”. Nuestra nación terminó con la esclavitud en 1865 después de una sangrienta guerra civil librada para proteger esa institución malévola, pero no dimos propiedad ni dinero a personas anteriormente esclavizadas por sus siglos de trabajo no remunerado.

¿Qué haría Jesús? Bueno, sabemos lo que hicieron los seguidores de Jesús. La Iglesia Episcopal del Sur ayudó a dar forma a la segregación de Jim Crow, y toda la iglesia estuvo mayoritariamente en silencio durante al menos un siglo sobre la segregación racial, de linchamientos, supresión de votantes, prácticas injustas de empleo, y otras formas de injusticia racial.

Pero durante los últimos 20 años, comenzando durante el episcopado de mi predecesor y colega actual como mi obispo asistente, el obispo Bob Ihloff, y nuestro antiguo Obispo Sufragáneo John Rabb, revelamos nuestra historia para llegar a la verdad. Miramos sin miedo nuestra historia diocesana y contamos la historia; y alentamos a nuestras parroquias a descubrir sus historias y contar sobre cómo se relacionaron con la comunidad afroamericana. Y sabes, a veces la verdad duele—pero escuchamos a Jesús decir, “La verdad también te liberará”. ¡Digan la verdad!

¿Qué haría Jesús? ¿Qué nos está diciendo? Aprendimos algo en la Escuela Dominical hace mucho tiempo: Si le robas algo a alguien, lo devuelves. Y si no puedes pagarlo todo, toma medidas para enmendarlo. Cuando comenzamos a mostrar cuánto ganó esta iglesia Caucásica de siglos de injusticia racial, eso simplemente no nos cayó bien. Eso se atascó en nuestro buche. Seguíamos escuchando a Jesús decir: “Paga la deuda que tienes con las comunidades Afroamericanas empobrecidas en este estado”.

Entonces, en la próxima convención diocesana votamos masivamente para iniciar un fondo inicial de $1 millón de dólares. Esa cifra no era un cálculo matemático, sino una cifra moral. Se toma de donaciones y otros fondos diocesanos y representa alrededor del 20% de nuestro presupuesto anual. Va a poner una mella en algunas otras cosas que queremos hacer; dolerá, y así debe ser. Porque lo debemos, se lo debemos a la comunidad afroamericana. Después de siglos de robar dinero de la comunidad Afroamericana, vamos a invertir en esa empobrecida comunidad. Estaremos financiando proyectos en educación, vivienda, salud, medio ambiente y desarrollo económico para sufragar parte de esa deuda.

La respuesta de la comunidad en general ha sido abrumadoramente positiva, para mi sorpresa, francamente. Esperaba más resistencia. Pero todavía estamos recibiendo cartas y cheques de personas en todo Maryland que dicen, “Gracias, Diócesis de Maryland, finalmente han admitido la verdad, y están actuando de acuerdo a sus convicciones. Adjunto hay un cheque; quiero ayudar.” Uno de esos regalos vino inesperadamente de una congregación muy pequeña en un pueblo minero de carbón, la Iglesia de San James en Westernport. Sus antepasados no tenían nada que ver con la esclavitud, pero querían estar en solidaridad con las comunidades afroamericanas pobres e insuficientemente invertidas, especialmente en las partes rurales occidentales de nuestra diócesis. Cuando los visité el año pasado, me enviaron un cheque por $10.000 dólares. Esa congregación Caucásica pequeña, en su mayoría rural. Eso es lo que hace el amor, y lo lograron.

Saben, con demasiada frecuencia queremos hacer una reconciliación a bajo costo. No queremos pagar el precio de reconciliarnos; lo queremos de gratis; deseamos que sea fácil y que todos sonrían. Pero si la reconciliación no cuesta nada, ¡entonces no vale nada! No hay reconciliación sin una rendición de cuentas, y el momento es ahora. Si no creen que es ahora, dígame cuándo; deme una fecha,—¿cuándo es el momento de la justicia? Creemos que es ahora. El pago de reparaciones es un juicio por los pecados raciales de nuestra nación y nuestra iglesia contra personas con bella piel oscura como la mía.

Y amigos, no dejen que voces y fuerzas retrógradas contra esta posición envenenen sus mentes y los asusten sobre lo que supuestamente significa la reparación. Las reparaciones no se tratan de gente Caucásica que le manda cheques al pueblo afroamericano. No, se trata de lo que esta generación hará para corregir una injusticia que las generaciones anteriores no hicieron. Carecían del valor para pagar a las personas anteriormente esclavizadas; seguían postergando el problema. Pero el problema persiste; no llegó a ninguna parte. ¿Mostrará esta generación suficiente coraje y fe, y amor para hacer lo correcto después de tantos años de decir, “simplemente no se puede lograr” o “las reparaciones nunca se materializarán en este país”? Bueno, tal vez para algunos, pero no para la gente Afroamericana.

Existe algo así como una “culpabilidad colectiva”. La experiencia de la Diócesis de Maryland con comunidades de ascendencia africana es diferente de la de Hawái, o Arizona, Minnesota, Taiwán, Centroamérica, o Puerto Rico. La respuesta de cada diócesis al racismo va a ser diferente debido a diferentes historias y contextos. Pero todos vivimos en un mundo donde las personas de piel más oscura son tratadas como “inferiores” en relación con las personas de piel más clara en todo el mundo.

Y todos nosotros pertenecemos a esta iglesia, que colectivamente se ha beneficiado financieramente de la esclavitud y la segregación racial. Sabemos, o debemos saber, la historia de cómo nuestra iglesia recibió porciones sustanciales de sus recursos financieros de fuentes racistas. Sabemos la verdad acerca de cómo la Sociedad para la Propagación del Evangelio (SPG por sus siglas en inglés) derivó gran parte de sus ingresos de las plantaciones de azúcar que hicieron uso del trabajo esclavo, y sabemos que dos de los fundadores de la Sociedad Misionera Doméstica y Extranjera (DFMS por sus siglas en inglés) también fundaron la Sociedad Americana de Colonización— de la cual Francis Scott Key, el autor de “The Star-Spangled Banner” (“Himno Nacionald e los EE.UU”) y un miembro de la junta parroquial en All Saints Church (La Iglesia de Todos los Santos) en Frederick, fue un prominente defensor de sus objetivos de deportar a las personas esclavizadas liberadas en este país—para deportarlas. Todos nos hemos beneficiado financieramente del racismo institucionalizado.

Algunas diócesis e instituciones ya han comenzado a abordar la responsabilidad; Maryland no es la única. Hay otras diócesis que ya han hecho compromisos de reparaciones o que están en alguna etapa de educarse; ustedes saben quiénes son, y quiero darles LAS GRACIAS; Maryland les agradece. Además de estos y otros esfuerzos diocesanos, esta convención votará sobre una resolución del Grupo de Trabajo de los Funcionarios Primados sobre Decir la Verdad, el Reconocimiento y la Sanación que pide el establecimiento de una Coalición Episcopal para la Equidad y la Justicia Racial como asociación voluntaria de diócesis, parroquias, organizaciones episcopales, e individuos. Amigos míos, es este tipo de propuestas audaces lo que hará que nuestra iglesia avance hacia la justicia racial por muchos años, y espero que ustedes las apoyen.

Todos somos necesarios para arreglar esto. No importa si sus antepasados vinieron a estas costas en el Mayflower o en un barco esclavo; no importa si eran esclavos o eran esclavizados, no importa si eres de una diócesis del Norte o una diócesis del Sur, o si estás en Europa, Asia o América Central; no importa si eres un inmigrante reciente o una familia que ha estado aquí durante generaciones—todos estamos en el mismo barco ahora. Estoy comprometido a ser parte de la solución; estoy pagando a nuestro Fondo de Reparaciones diocesano, aunque mi país y mi propia iglesia hayan esclavizado a mi pueblo. Sus protestas de que no son racistas y no tuvieron nada que ver con el hecho de que millones de Afroamericanos están atrapados en la pobreza sistémica, son argumentos que para mí no tienen peso. Todos hemos heredado un caos racial; nadamos en un océano de racismo en este país, y los peces no saben que están mojados. No lo hemos causado, pero tenemos que arreglarlo. La reparación no se trata de culpa, sino de responsabilidad. Todos tenemos la responsabilidad de reparar los daños causados por siglos de robo.

Quiero dejarles con una foto que hice cuando hice mi primera peregrinación a Tierra Santa desde esta diócesis en 2008. Es una foto de una sección del muro en Jerusalén, ese muro de separación, donde alguien pintó estas palabras: ¡JESÚS DERRIBARÁ ESTE MURO! Y así lo hará. Ese muro desaparecerá; siempre es así. Nuestro Señor nos está invitando a unirnos a Él en esta labor. Así que, amigos, manos a la obra. Reconstruyamos nuestras comunidades con los recursos que tenemos. Tomemos grandes pasos para derribar todos los muros de inequidad e injusticia y empezar a construir puentes a través de las divisiones en nuestras comunidades, en nuestras iglesias, en nuestras diócesis y en toda la Iglesia Episcopal. Y al hacerlo, demos todo honor y gloria a Dios, ahora y para siempre. Amén.