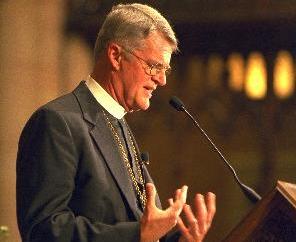

One of my great privileges serving as your presiding bishop and primate, and indeed one of the things I will miss most once I relinquish this ministry in November, is my unusual opportunity to come to know something of how God acts in the lives of fellow Christians who are seeking, in a wide variety of contexts, to be ministers of Christ’s reconciling love.

Near the end of July, I participated in a conversation with a cross-section of other heads of provinces of the Anglican Communion. We gathered at Coventry Cathedral under the auspices of the Community of the Cross of Nails, a worldwide organization committed to the ministry of reconciliation. On Nov. 14, 1940, this industrial city in the Midlands of England was almost obliterated by bombs and the cathedral was reduced to ruins. Its ancient walls still stand, but beside them a new cathedral has risen up as a sign of and center for reconciliation.

The conversation amongst the primates was first conceived last January as a way to reflect upon the future of our shared life of communion and ways in which we within and among our provinces can enable an ongoing ministry of reconciliation. Over the course of several days, we spoke candidly and listened carefully to one another.

As we parted at the end of an extremely fruitful time to return to our very different contexts, we agreed that our days of conversation had been a positive contribution to the future of the communion. The day after I returned to the United States, I traveled to a gathering of alumni who have participated in our Young Adult Service Corps, a program of the Episcopal Church that offers one-year missionary assignments in various parts of the Anglican Communion.

The purpose of the gathering, at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, was to provide an opportunity for those who had participated in the program to reflect on their experiences. What struck me most as I listened to these dedicated and faithful young men and women was that, though their assignments had taken them in different directions around the globe, their experiences had a remarkable similarity.

In spite of whatever difficulties they experienced, whatever dispossession they had undergone in terms of attitudes and ideas, they viewed their term as a life-changing time of growth and transformation. They spoke of the sense of hope in those they worked among: hope often in the midst of seemingly hopeless situations of poverty and conflict. Such hope was a stark contradiction to their outer circumstances and revealed a capacity for endurance in our Anglican brothers and sisters.

This spoke profoundly to the young adults from the United States, who had not been obliged to put their own endurance to such severe tests. At one point a young man made the following observation: “The purpose of the church is to guard hope.” I was struck by this comment. What does it mean that the purpose of the church is to guard hope? It certainly doesn’t mean the church is meant to be cheerfully optimistic in the midst of life-denying circumstances.

I believe it means that the church is obliged to live in such union with Christ that Christ’s hope becomes our own. Just as the Spirit weaves the love of Christ into the depths of our being, so, too, that same Spirit works in us the mystery of hope. I came away from my time in Amherst pondering the mystery of hope and reflecting back on my conversations with the primates in Coventry. The primates’ conversations brought us to a shared hope in the future of our communion and its mission to the world.

Our sense of hope had nothing to do with optimism or trying to avoid a difficult reality at hand, either by denial or the projection of some happy and pain-free future. It was not based on a superficial spirit of polite cordiality, but rather was deeply grounded in our union in Christ.

“The answer is in the pain” is a principle of spiritual growth. And indeed, often in the midst of the most desperate of situations a confidence and a deep knowing emerge – beyond how or when – that, in the words of Julian of Norwich, “All shall be well and all manner of things shall be well.”

Curiously, we find our spring of hope in the midst of what is seemingly hopeless. Hope is a gift bestowed when we most deeply and truthfully confront and acknowledge the very things that seem to us to leave us in dark despair.

I have been richly blessed in these two experiences, one after another: meeting with the primates and the young missionaries. In both of these groups of faithful and struggling Christians I saw a spirit of candor and receptivity and a willingness to face into things that we find most painful and difficult.

I also saw wellsprings of hope. As I gave thanks for this, I found myself recalling St. Paul’s prayer: “May the God of hope fill you with all joy and peace in believing, so that you may abound in hope by the power of the Holy Spirit.”

This is my prayer for you, for all of us, for our church and our communion.