Misinformation, Disinformation, Fake News: Why Do We Care?

- Introduction

- Definitions

- Understanding Information Disorder and Disinformation Campaigns

- Who Creates and Spreads Misinformation?

- On Elections

- What Can I Do?

- On the U.S. 2020 Census

- On COVID-19

- On the Dangers of Government-Sponsored Disinformation

- On Vaccines

- On Climate Change

- A Reflection on Misinformation, Free Speech, and Democracy

- Conclusion: Seeking Truth

Introduction

It can be tempting to think that the fear-inducing, hyper-partisan, misleading, and outright false content pervasive today is an exclusively modern problem. Yet for thousands of years, our Jewish and Christian ancestors have taught that deception is as old as humanity itself. In Genesis 3, the serpent manipulates Eve through a series of misleading and half-true statements to eat the forbidden fruit, then makes Adam do the same by offering him the choice through a trusted source. Sound like anything that has crossed your social media feed recently?

As Christians, we are not called to a life of half-truths and deception. We are called to follow a God who is “the way, the truth, and the life” (John 14:6). The Prayer Book also teaches that among our duties to our neighbors is “to be honest and fair in our dealings” and to “speak truth, and not mislead others by our silence.” (pg. 848) Let us therefore examine our own conduct to limit the spread of deceitful information and call upon our leaders to work towards the same.

The rapid expansion of digitalization and online platforms has enabled deceitful content to spread more rapidly and disguise itself more effectively. The nonprofit First Draft News has excellent language describing what information manipulation looks like today:

“The term ‘fake news’ doesn’t begin to cover all of this. Most of this content isn’t even fake; it’s often genuine, used out of context and weaponized by people who know that falsehoods based on a kernel of truth are more likely to be believed and shared. And most of this can’t be described as ‘news’. It’s good old-fashioned rumors, it’s memes, it’s manipulated videos and hyper-targeted ‘dark ads’ and old photos re-shared as new.

At First Draft, we advocate using the terms that are most appropriate for the type of content; whether that’s propaganda, lies, conspiracies, rumors, hoaxes, hyperpartisan content, falsehoods or manipulated media. We also prefer to use the terms disinformation, misinformation or malinformation. Collectively, we call it information disorder.”

Go farther! Take the ChurchNext course “Spiritual Truth in the Age of Fake News” with Elizabeth Geitz and Rebecca Cotton

Definitions

| Information Disorder: a term coined by First Draft News to encompass the spectrum of misinformation, malinformation, and disinformation Misinformation: false content that the person sharing doesn’t realize is false or misleading Malinformation: genuine information shared with an intent to cause harm Disinformation: shared content that is intentionally false and/or misleading and designed to cause harm Social Cybersecurity: the science to characterize, understand, and forecast cyber-mediated changes in human behavior, social, cultural and political outcomes |

Some disinformation is entirely false and fabricated, like this “news” article claiming Pope Francis has coronavirus. As this twitter user points out, the domain was registered several years ago in China and suddenly changed a couple of days previously.

https://twitter.com/cindyotis_/status/1233771696462684161

Bots can be used to amplify fringe messages to mainstream audiences. Russian trolls, sophisticated bots, and “content polluters” tweet about vaccination and anti-vaccine messages like this one at significantly higher rates than average users. An estimated 25% of climate denial tweets are spread by bots.

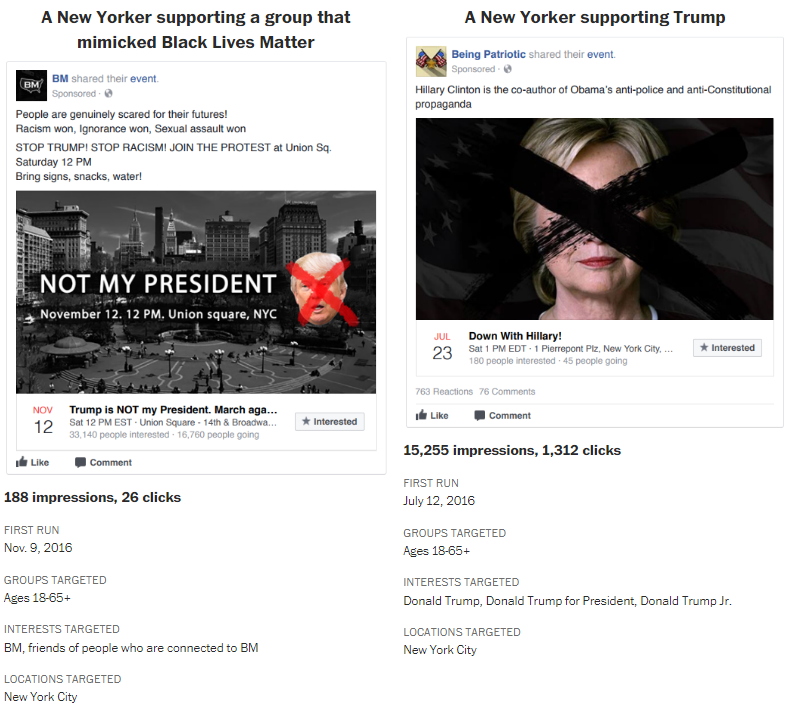

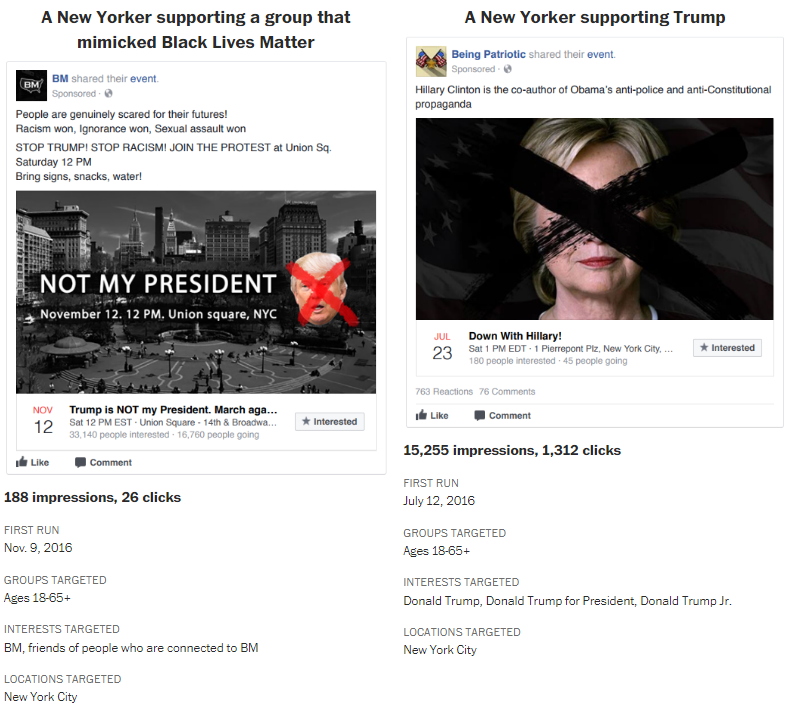

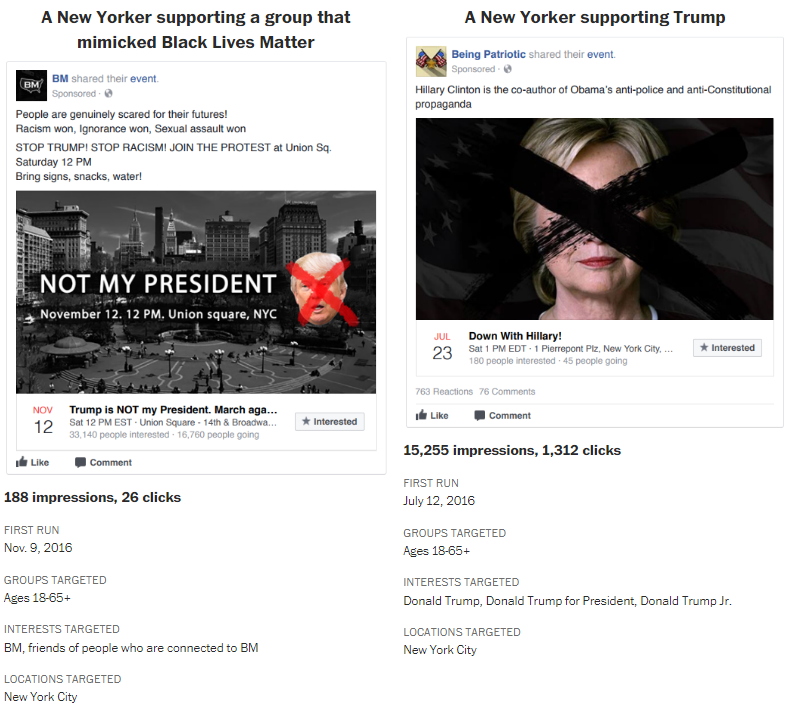

One particular example of concern involves Russian intelligence services using paid advertisements during the 2016 U.S. election that sent different audiences different targeted messages. While national governments have long-used misinformation against enemies, social media has fundamentally changed the scope and reach of these campaigns. The goal of the ads was to widen existing divisions in the U.S., not simply to promote contradictory messages. Notable use of inflammatory language and images and deliberately-misleading names of Facebook pages contributed to the confusion—nothing shows these ads were paid for by foreign actors.

Source: https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2017/business/russian-ads-facebook-targeting/

Understanding Information Disorder and Disinformation Campaigns

Roughly 4 in 10 Americans say they often come across made-up news and information. Although the emerging field of social cybersecurity is just now starting to gauge how information disorder affects individuals and society, we have a fairly good understanding of how manipulated information is spread.

Disinformation campaigns are deliberately crafted to spread false or misleading information. However, it may not be the case that the campaign message itself is the actual goal. A common tactic is to first identify two pro/con groups on a divisive issue (abortion, vaccinations, climate change, and political ideology are prime examples). An effective disinformation campaign would infiltrate both sides, backing group leaders, and helping to develop echo chamber qualities in the group. In echo chambers, group members sideline outside information, pass internal information extremely quickly, and make decisions based on emotion and “what everyone knows.” Campaigns use this emotion-based decision-making to incite feelings like dismay or excitement in both groups, then pit the two sides against each other. Ultimately, both suffer from a lack of cross-issue communication and lose even more trust in “the other,” in short, enlarging the divide between the two sides.

Researchers are extremely concerned that disinformation campaigns undermine democratic processes by fostering doubt and destabilizing the common ground that democratic societies require. “[It’s like] listening to static through headphones,” says Dr. Kate Starbird, professor at the University of Washington. “It is designed to overwhelm our capacity to make sense of information, to push us into thinking that the healthiest response is to disengage. And we may have trouble seeing the problem when content aligns with our political identities.”

Who Creates and Spreads Misinformation?

Most misinformation you see is created and spread by seven types of actors: jokers, scammers, interest-driven entities, conspiracy theorists, “insiders”, celebrities, or your friends and family. We have discussed the function of many of these actors elsewhere in our misinformation resource, but we have not yet touched upon the role of insiders, conspiracy theorists, and celebrities as sources and spreaders of misinformation.

Insiders, or those who reveal confidential information to the general public, are often seen as controversial figures. Yet a rising number of “insiders” aren’t true insiders at all: they are merely individuals claiming false credentials to lend credence to their disinformation. At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown, messages about coronavirus “cures” and preventive measures claimed authority from Taiwanese experts, Japanese doctors, and the Stanford hospital board. However, these messages–which were almost always false and sometimes harmful–had not been authored or endorsed by any of the experts listed. When evaluating a potential insider’s trustworthiness, be suspicious of vague credentials or information passed by “a friend of a friend.” A genuine whistleblower who has shared their concerns though proper channels might well be entitled to anonymity. Someone sharing claims through social media or email probably isn’t.

There’s a significant chance you believe or find credence in at least one conspiracy theory: over 60% of Americans do. Conspiracy theories, somewhat counterintuitively, offer rationality in a random and unpredictable world. According to John Cook, an expert on misinformation with George Mason University’s Center for Climate Change Communication, “it gives people more sense of control to imagine that, rather than random things happening, there are these shadowy groups and agencies that are controlling it. Randomness is very discomforting to people.” Conspiracy theories flourish in the wake of cataclysmic events like a pandemic or bombing and can be almost impossible to disprove. Since most conspiracies include belief in some kind of cover-up, refutations of or jokes about a conspiracy theory simply provide more “evidence” that a cover-up is being perpetuated.

Audiences that mostly consume mainstream media see far more false insider stories and conspiracy theories than they might realize. While mainstream media itself remains highly reliable, online algorithms that favor content with high engagement instead of content with high veracity make it easier to transmit misinformation to these audiences through widely-used platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube. Highly-profile individuals like celebrities are a key facilitator for this type of misinformation spread. When examining how COVID-19 misinformation travels, for example, misinformation posts from celebrities, politicians, and other prominent public figures comprised almost 70% of the total social media engagement, even though those posts represented only 20% of the total COVID-19 misinformation content. This type of engagement uses the logical fallacy of appeal to authority: an individual’s high visibility on social media does not mean they have the expertise to evaluate whether everything they see and share is true.

On Politics and Conspiracy Theories

Increasingly, both alt-left and alt-right conspiracy theories are being seriously discussed in political circles as legitimate concepts. This trend is particularly concerning given the potential influence of this misinformation on lawmakers and the legislation they authorize. However, far-left and far-right conspiracies aren’t being promoted in the same manner: far-right conspiracies are more likely to be spread by concerted networks into mainstream channels, giving them a further reach and increased perceived legitimacy. Regardless of political orientation, we should strive to carefully evaluate all information that will affect our systems of government and avoid using unsubstantiated speculations to determine policy.

On Elections

Elections and politics have always involved disinformation and manipulation. Often, a politician’s ability to effectively use and counter such strategies is a mark of political competency. Consider Odysseus, “the man of twists and turns,” whose cleverness and trickery was praised by men and gods in the Greek epics The Iliad and The Odyssey. Yet democratic societies rely on fair and free elections to ensure that government derives its authority from the will of the people. Disinformation campaigns aimed at voters undermine the ability of a country to hold fair and free elections. There are number of tactics used for this goal.

Microtargeting of communities is particularly concerning: how can an election be fair if one community receives highly targeted, misleading messages urging them to vote for or against a candidate? Or worse, what happens when targeted messages advertise the incorrect time, place, or method of voting to a particular group, like the “Text to Vote for Hillary” ads? Even the threat of such actions undermines confidence in democratic systems.

We now know that for the past few years targeted international digital campaigns in the U.S. and around the world have worked to spread intentionally inaccurate content, undermine faith in election procedures, and widen existing fissures in multiple countries. Yet even U.S. domestic organizations are increasingly using these same disinformation techniques for short-term election or politically-motivated gains. Ultimately, election disinformation pushed by all actors weakens the democratic system.

The Episcopal Church recognizes the process of voting and political participation is an act of Christian stewardship, and that such processes must be fair, secure, and just (see resolutions EC022020.16 and 2018-D096). Since misinformation threatens this process, The Episcopal Church calls upon all its members to be vigilant when engaging with online information and encourages the use of fact-checking and source identification to limit misinformation’s spread. Further, we urge Episcopalians to hold government officials accountable for limiting the spread of information that is false and designed to cause harm.

What Can I Do?

Misinformation often spreads faster than real news and reaches a wider audience. It’s also becoming increasingly difficult to identify. The first step in addressing misinformation is acknowledgement: all of us contribute to the problem, and we must all take ownership to stop it. As long as misinformation remains an issue for “the other” to solve—Gen Z, Boomers, Facebook, Millennials, in-laws—it will persist.

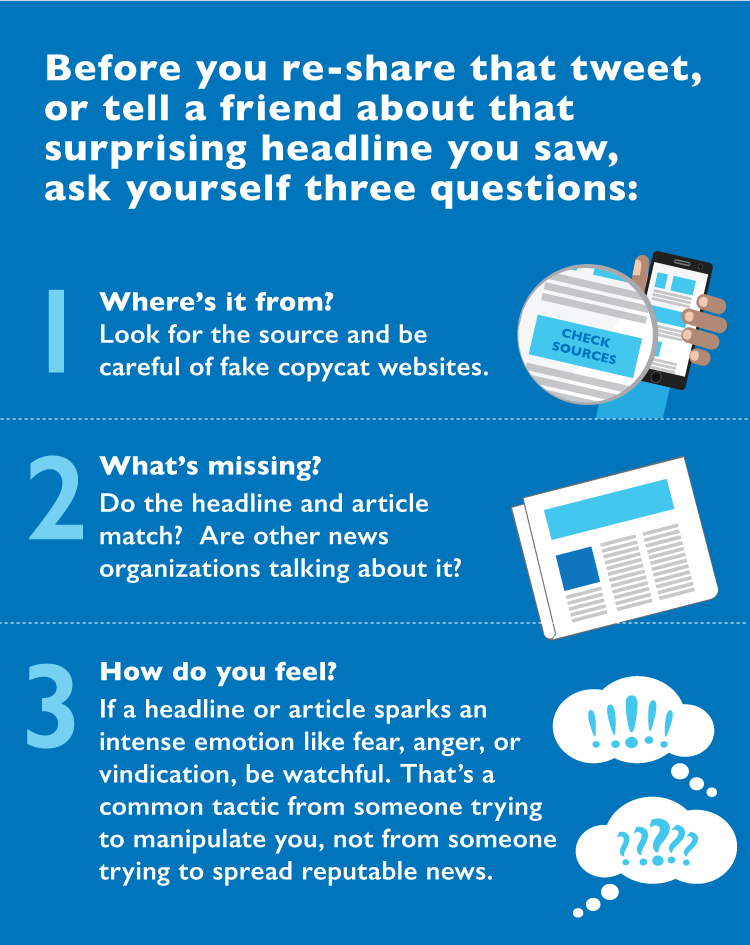

We won’t catch all the misinformation streaming past us. But before you re-share that tweet, or tell a friend about that surprising headline you saw, ask yourself three questions:

- Where’s it from? Look for the source and be careful of fake copycat websites.

- What’s missing? Do the headline and article match? Are other news organizations talking about it?

- How do you feel? If a headline or article sparks an intense emotion like fear, anger, or vindication, be watchful. That’s a common tactic from someone trying to manipulate you, not from someone trying to spread reputable news.

Other things to consider:

- Learn who to trust. An unfortunate consequence of disinformation vigilance can be censorship through noise. If vigilance leads us to distrust every headline, then those promoting disinformation are succeeding. This means we are less likely to receive information that is accurate and informative. Learning who generally produces accurate information is as important as carefully examining unknown sources.

- Genre matters. It’s not just satirical Onion articles that get shared as a “news.” Be mindful of the differences in presentation, fact-checking protocol, and accountability standards between peer-reviewed research, fact-checked news articles, personal opinion pieces and talk shows, and various forms of satire, propaganda, and gossip.

- One effective way to end disinformation campaigns is to label them. While you might not want to engage with the comment thread debates on social media, consider making a comment or sending a private message to friends and family members when they share a post that you suspect is false or misleading. And be responsive to the same feedback from others!

- Communicate to elected officials that protection from disinformation campaigns is important to you.

- Consider asking your members of Congress to support election security. Bills debated in the 116th Congress include the DETER Act S. 1060, Honest Ads Act S.1356/H.R.2592, and SHIELD Act H.R. 4617.

- Develop a nuanced understanding of the relationship between free speech and disinformation. Consider: Does (or should) the Constitution offer paid commercial or political ads the same free speech protections as individuals? Does freedom of speech also include the freedom to receive information? If so, does disinformation threaten that right? Who (if anyone) should be responsible for tracking/tagging false information? Should there be limits to web anonymity or author disclosure requirements? Read “Countering Misinformation with Lessons from Public Health.”

Further Resources

If you want to learn more about information disorder, here are some recommendations:

- Understanding Information Disorder – a thorough but very readable examination of the modern information disorder landscape

- The Full Fact Toolkit – How to quickly spot possible misinformation before sharing it. Also includes links to numerous fact-checking websites

- Foreign Interference and the 2020 Election

- Bot Sentinel – Resource that lets you see what topics are trending on suspected bot twitter accounts by day/hour. You can also put in any twitter handle and get a score on whether it looks like a suspected bot account.

- Quizzes to see how well you spot misinformation!

- News articles

- Social media posts

Resolutions by General Convention and Executive Council

- 2022-D063 – Support Policies to Combat Media Disinformation

- EXC062016.07 – Support for Campaign Finance Reform

- Resolution 2018-D096 – Urge Advocacy for Good Governance and Fair Participation

On the U.S. 2020 Census

Every 10 years, the US government undertakes a massive effort to count all individuals living in the country. This count is critically important: it determines representation in Congress, is used to allocate federal funds for the next decade, and provides valuable information for state and local community officials, service providers, and private businesses. Misinformation about the census is easily spread and incredibly damaging. Communities where census misinformation is most rampant are often ones with “hard-to-count” subgroups who have the most to gain from accurate population counts.

Targets of census misinformation often include:

- Data privacy and financial scams. What you need to know: The Census Bureau will never ask for your Social Security number, credit card or bank account numbers, or a financial donation.

- In-person census takers. What you need to know: During the spring and summer of the 2020 Census, in-person census takers will visit homes to follow up with individuals who have not yet responded. All workers carry an ID badge with their photograph, a U.S. Department of Commerce watermark, and an expiration date. If you have questions about their identity, you can call +1-844-330-2020 to speak with a Census Bureau representative.

- Data privacy and protection guarantees. What you need to know: Under Title 13 of the U.S. Code, census data may ONLY be used for statistical purposes. The Census Bureau cannot release any identifiable information about you, your home, or your business, even to law enforcement agencies.

You can learn more about Census Misinformation and how to counter it on the official U.S. Census website. Also, don’t miss the Office of Government Relation’s Census Series and census engagement toolkit!

On COVID-19

The uncertainty and fear surrounding COVID-19 create a perfect environment for misinformation about it to spread rapidly and widely, so much so that the World Health Organization (WHO) has warned fighting this disease will also require fighting an “infodemic.” Misinformation topics include the origins of the disease, how it spreads, how to treat it, authorities’ responses, and communities’ actions. Individuals in the U.S. and abroad have already died from following false advice about coronavirus treatment and prevention methods.

Amid this infodemic, the Office of Government Relations urges everyone to obtain and share information about the coronavirus disease directly from the World Health Organization, the Center for Disease Control, John Hopkins University, or your local health care providers. We know that guidance from these agencies can fluctuate and sometimes change completely. Understand, however, that this is because these agencies are doing their due diligence to provide transparency to the public about this health crisis and to adjust their recommendations as new scientific research comes in.

What is going on with the masks?

Our health care workers directly interacting with many COVID-19 patients have some of the highest risk for catching this disease and are one of the most important groups to keep healthy and at work. Because of this, the limited supply of N95 and surgical masks are being directed towards this group. Other face covers, including homemade ones, are not very good at protecting people from COVID-19 and other infectious diseases, which is why the CDC did not originally recommend the general public wear them. However, these lower grade masks can reduce the spread of COVID-19 from individuals who are already infected. As data came out that many COVID-19 cases were being spread by individuals who did not know they had the disease, the CDC changed its mask recommendation to encourage the general public to wear one. Wearing a cloth mask won’t directly stop you from getting sick, but if you and everyone around you wears one, you are far less likely to spread the disease to one another.

What else should we be doing?

Current health guidelines are mundane but still very important to follow. Best practices recommended by the CDC for everyone currently include:

- Wash your hands often

- Avoid close contact

- Cover your mouth and nose with a cloth face cover while around others

- Cover coughs and sneezes

- Clean and disinfect

For individuals infected with COVID-19, we know that there are various suggestions to alleviate symptoms at home. Look out for treatments with potentially dangerous side effects and remember to track any medication you take, including natural or herbal supplements. If your condition worsens, this information will help your doctor know how to best treat you.

As we fight this global pandemic, let us ensure our actions are limiting the spread of this disease, not increasing the spread of misinformation.

On the Dangers of Government-Sponsored Disinformation

Government-sponsored disinformation campaigns have the power to be damaging to society. Usually, individuals have some say in the amount of social media they consume and which organization they choose to receive news from. But since governments are our law-making bodies with the power and authority to enforce those laws, all of us must pay attention to government-sponsored information campaigns. If these campaigns are used to spread false or misleading information to citizens, especially if the deception is intentional, societal damage begins to accumulate. Here’s how:

1. Erosion of trust.

Government-backed disinformation can erode trust between branches of government, between a government and its citizens, and in the international sphere. Americans, for example, have less trust in the federal government than in state or local government, and they also believe the federal government is less likely to provide fair and accurate information. This lack of trust makes it much harder to coordinate efforts like disaster relief and health care recommendations while also opening the door for other actors with less oversight and accountability to become primary information providers. In democratic societies that rely much more explicitly on a level of trust between elected officials and constituents, erosion of trust can represent a long-term threat to stable government systems.

2. Lack of accountability.

No authority wants to be responsible for a failed initiative, poor disaster response, or other crises where the government is perceived to have managed the situation badly. Disinformation campaigns can allow governments to shift blame to other scapegoats or deny a problem’s existence altogether while avoiding productive action to address the issue.

3. Encourages the spread of more misinformation.

Disinformation campaigns often produce short-term benefits, though the long-term repercussions may ultimately hurt the government sponsoring the campaign. Once one government starts to rely on disinformation, it therefore becomes attractive for other domestic and foreign interests to spearhead their own campaigns either through a “they-do-it why-shouldn’t-I” rationalization or out of a desire to remain competitive in the information sphere of influence.

On Vaccines

Vaccines are one of the greatest medical accomplishments in history: extraordinarily safe, incredibly effective, and once past the initial development, often inexpensive to produce. Vaccines have saved millions of lives and protect an even greater number of individuals from life-long debilitating medical conditions that can result from a severe case of an infectious disease. In today’s COVID-19 world, experts predict that life likely will not return to “normal” until a vaccine is developed and can be widely distributed.

An anti-vaccine movement has persisted almost since the invention of vaccines. Following the introduction of the smallpox vaccine in the 1800s, anti-vaccine movements spread across Britain and the United States fueled by a skepticism of science, disapproval and fear of the vaccine method, and an objection to personal liberty infringements when legislation mandated vaccinations. More recently, a fraudulent study published in 1998 purported a link between the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine and autism. This paper, and others like it, have contributed to thousands of parents choosing not to vaccinate their children, despite investigations showing data from the study was falsified and the main author failed to disclose a significant financial conflict of interest.

Anti-vaccine misinformation is incredibly pervasive and easy to find in today’s media-rich culture. Platforms give discredited former scientists and doctors, such as the lead author of the fraudulent MMR vaccine study, a way to spread their views to a wide audience with very little oversight or accountability.

It is true that vaccines, like any medication, sometimes result in unexpected side effects. However, serious side effects from standard vaccinations are incredibly rare and far less likely to occur than serious side effects that can develop from contracting an infectious disease. Doctors further limit the likelihood of serious side effects by not vaccinating the small percentage of the population who are at higher risk of experiencing a negative reaction.

Choosing not to vaccinate for a non-medical reason does not just put in the individual in question at risk: it also creates an environment for infectious diseases to spread to those who, for health reasons, cannot get vaccinated and are often at risk for developing more serious symptoms of a disease. Because refusing vaccinations brings significant public health risks to many members of the community, U.S. courts have generally upheld states’ authority to mandate vaccinations, noting that an individual’s right to personal liberty or religious freedom does not supersede a state’s responsibility to safeguard the public. Approximately 1.5 million people die from vaccine-preventable diseases each year. In an effort to protect all its members and our neighbors, The Episcopal Church does not recognize theological or religious exemptions for vaccines and requires vaccinations for all participants and staff at Episcopal events (except for those with a medical exemption). Learn more about engaging faith communities on immunization from The World Faiths Development Dialogue.

If you have questions about vaccines:

- Talk with your primary health care provider. They can explain possible vaccine side effects, possible side effects from catching a disease, and the relative risks of each. Your primary health care provider should also be informed of any pre-existing medical conditions you or your children have.

- Conduct online research from reputable sources, like the Centers for Disease Control. There’s a lot of false, misleading, or incomplete information about vaccinations. Make sure any information you use has been thoroughly vetted by the medical community.

On Climate Change

Disinformation is not the only reason for climate change denial in the U.S., but it is certainly a major contributor. According to climate scientist Dr. Katherine Hayhoe, the 6 stages of climate denial can be summarized as follows: “It’s not real. It’s not us. It’s not that bad. It’s too expensive to fix. Aha, here’s a great solution (that actually does nothing). And – oh no! Now it’s too late. You really should have warned us earlier.”

In 1856, amateur scientist Eunice Foote published a paper in the American Journal of Science about her discovery of the heat-trapping properties of carbon dioxide and theorized that an atmosphere with a higher concentration of CO2 would result in a warmer Earth. A century and a half later, the science has only become more clear: climate change is real, humans are causing it, and solutions must be implemented as quickly as possible. A growing scientific consensus, however, was paralleled by a growing body of climate misinformation funded by the fossil fuel industry and private philanthropy. We should be having conversations about solutions to climate change and what compromises are necessary to implement them. Instead, we continue to debate what is already scientific consensus and strive to correct the errors misinformation propagates.

Political affiliation—not scientific knowledge—is a key predictor of an individual’s belief in climate change in the U.S. This partisan divide, fueled by misinformation, has stalled bipartisan legislation to address climate change for over 20 years. To this day, very little action has been taken at the federal level to decrease the United States’ carbon footprint. Even within the environmental community, climate misinformation persists: an environmental documentary released around Earth Day 2020 received scathing reviews for mixing important questions about the renewable energy sector with an enormous amount of outdated, misleading, and false data.

Climate change is already one of the most difficult crises of our time that we need to address. Let’s not make it more difficult to implement solutions by using misinformation to disguise the problem and derail debates.

To learn more about the science of climate change:

To learn more about climate change solutions:

- Project Drawdown

- Climate Interactive En-ROADS Simulator

- Office of Government Relations Creation Care Resources

- The Episcopal Church Creation Care Ministry

A Reflection on Misinformation, Free Speech, and Democracy

In the Christian faith, words are powerful. God’s spoken word in Genesis commands the universe into being, and John identifies Jesus as this spoken word in the very beginning of his gospel: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God” (John 1:1).

Our country’s founders also recognized the power of words and protected it in the first amendment to the U.S. Constitution: the government “shall make no law” abridging “the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of people peaceably to assemble.” Through the years, the courts have mostly upheld this protection, including for forms of speech that many Americans find objectionable like sexually explicit material and hate speech. Although speech, like any tool, can be used for good or malicious purposes, U.S. law and the courts have ruled that, in almost all cases, the response to “bad” speech should be corrective speech and dialogue, not censorship.

While free speech is an incredibly important tool to safeguard democracy, it can also be weaponized to undermine it. Barring a small category of speech like libel and information that puts someone’s life at risk, free speech protections in the United States make no distinction between true and false information: both are protected under the law. In today’s online media landscape where everyone can be a publisher, it becomes possible for concerted campaigns to enact “censorship through noise,” obscuring the truth through sheer volume and propaganda of false ideas.

Remember: words have power. Most of us know the adage, “Don’t trust everything you see on the internet.” But our brains remember content we see most often without categorizing it as “fact” or “possible misinformation.” In a censorship through noise ecosystem, a large percentage of what we see and hear on the internet—and therefore remember—is misinformation. Some of us might accurately categorize this misinformation as false. Some of us may incorrectly accept it as fact. Neither of us has the actual truth stored in our memory: censorship was accomplished.

Democracy relies on informed, educated voters being able to select representatives who will uphold their interests. Both direct censorship and censorship through noise threaten voters’ ability to be informed about candidates and issues. Finding a way to limit misinformation without resorting to censorship is therefore crucial to protecting democracy.

The Role and Limitations of Media Gatekeepers

Online platforms have unique powers and protections conferred to them by Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act that are not held by traditional media gatekeepers. Lawmakers recognized in the 1990s that third-party users could pose a difficult challenge to internet platforms. Consider a website—anything from Facebook to a small blogger—that wants to let visitors post comments. What happens if a visitor posts sexually explicit material or something illegal? Is the website liable if they moderate—or fail to moderate—this content?

Lawmakers’ solution to this problem gave internet platforms two things:

- Liability protection from third-party content on their platform

- Ability to voluntarily exercise good faith editorial discretion on third-party content, like deleting a post with curse words. This editorial discretion also makes it perfectly legal for the platform to moderate content in a way that promotes a political, moral, or social viewpoint.

There is bipartisan support to rework Section 230. Good faith editorial discretion, for instance, should probably not rest solely in the hands of multinational online platforms that have no legal obligations to protect free speech (the first amendment only limits government actions around free speech, not actions of corporations or individuals). This is especially true for online platforms that act like publishers but are not held to the same standards as print, radio, or television publishers.

The Episcopal Church has limited policy on these issues to facilitate any advocacy on the matter, but given its relevance and our history of educating Episcopalians on misinformation, we have complied a variety of sources who propose legislative solutions to this problem in hopes of sparking constructive discussion.

Resources

- Public Knowledge – Going Beyond Section 230

- The New York Times – The First Amendment in the Age of Disinformation

- American Bar Association – The Ongoing Challenge to Define Free Speech

- The Heritage Foundation – Section 230: Mend It, Don’t End It

- The United Nations – Government Policy for the Internet Must Be Rights-Based and User-Centered

Conclusion: Seeking Truth

2 Kings 18 narrates a brilliant piece of misinformation from an Assyrian commander during King Hezekiah’s reign. The Assyrian army had already defeated the northern kingdom of Israel and many cities in the southern kingdom of Judah. While laying siege to Jerusalem, the Assyrian commander begins to taunt the Israelite soldiers on the city walls. “Do you think I’ve come up here to destroy this country without the express approval of God?” he asks. “The fact is that [your] God expressly ordered me, ‘Attack and destroy this country!’…Don’t let Hezekiah fool you; he can’t save you…Listen to the king of Assyria—deal with me and live the good life; I’ll guarantee everyone your own plot of ground—a garden and a well!…You only live once—so live, really live!” (The Message, 2 Kings 18:25-32) Yet the Israelite soldiers were silent and did not surrender the city.

Much like the Israelite soldiers, there isn’t much we can do to avoid exposure to misinformation—it’s constantly being shouted at us. The Israelite soldiers could ignore the Assyrian commander’s propaganda, however, because they had other sources they could trust to provide them with better information: King Hezekiah, Hezekiah’s advisors, and the prophet Isaiah, who assured the people that God did not seek Jerusalem’s destruction. Curating our own trusted sources can similarly allow us to find truth in the misinformation landscape.

When creating or growing your list of trusted sources, here are some things to keep in mind:

- Seek high standards of journalism and reporting. Content should be well-researched, authors, biases, and conflicts of interest should be disclosed, and errors should be promptly corrected.

- Understand and look for a clear delineation between genres. News (facts of what happened) is different from analysis (why something happened), and both differ from opinion (personal view—often from a non-expert—about why something happened). Citizen journalism (the collection, dissemination, and analysis of news and information by the general public) is rarely subjected to pre-publication vetting, making it a prime disinformation disseminator. There’s nothing wrong with consuming these various genres, but they should be evaluated differently.

- Use a diversity of lenses. There is no such thing as an “unbiased” view. So, follow both a liberal and a conservative news source—understanding both sides doesn’t mean you agree with both. Support local news to stay informed about your community. Read an international publication to follow global affairs. Follow industry or academic experts in fields that interest you.

Consuming high-quality, diverse media improves our understanding of the world and equips us to identify and critically evaluate misinformation. Even if you don’t follow every trusted source closely, knowing where to go to find accurate information or a different perspective about a topic is extremely helpful.

Why Trust Science?

It can be difficult to contextualize the truth that science provides. Scientific studies are written in a formulaic format that is unfamiliar to many of us and their results are not always clearly and accurately communicated by the media. So why do we trust science?

Scientific understanding is dynamic: it changes over time to incorporate new evidence and tests old assumptions to evaluate their validity. The iterative scientific method refines hypotheses so they better explain observations in the real world. Statistical analysis protects against the human tendency to see patterns and causality where none exists. The peer-review process safeguards the wider community from one researcher’s bias or errors.

The Episcopal Church supports the use of science “to inform and augment our understanding of God’s Creation, and to aid the Church in developing Christian programs and policies consistent with our faith.” We trust science because it offers a way to cross-check and examine our understanding of the world and to make informed decisions about how to live in a way that honors God and shows love to our neighbor.

—

Work on this resource was led by Rebecca Cotton, policy fellow, Office of Government Relations

La información errónea, la desinformación y las noticias falsa: ¿Por qué nos importa?

- Introducción

- Definiciones

- Comprensión del desorden de la información y las campañas de desinformación

- ¿Quién crea y difunde información errónea?

- Sobre las elecciones

- ¿Qué puedo hacer?

- Otras cosas a considerar:

- Recursos adicionales

- Sobre el censo de EE. UU. 2020

- Sobre COVID-19

- Sobre los peligros de la desinformación patrocinada por el gobierno

- Sobre las vacunas

- Sobre el cambio climático

- Una Reflexión sobre la Información Errónea, la Libertad de Expresión y la Democracia

- Conclusión: buscando la verdad

Introducción

Puede ser atractivo pensar que el híper partidista, engañoso y absolutamente falso contenido que induce el miedo y es omnipresente hoy es un problema exclusivamente moderno. Sin embargo, durante miles de años, nuestros antepasados judíos y cristianos han enseñado que el engaño es tan antiguo como la humanidad misma. En Génesis 3 la serpiente manipula a Eva a través de una serie de declaraciones engañosas y medias verdades para comer la fruta prohibida. Luego hace que Adam haga lo mismo ofreciéndole la opción a través de una fuente confiable. ¿Suena como algo que haya cruzado recientemente sus redes sociales?

Como cristianos, no estamos llamados a una vida de medias verdades y engaños. Estamos llamados a seguir a un Dios que es “el camino, la verdad y la vida” (John 14:6). El Libro de Oración Común también enseña que entre nuestros deberes con nuestros vecinos está “ser honestos y justos en nuestros tratos” y “decir la verdad y no engañar a los demás con nuestro silencio”. (pg. 848) Por lo tanto, examinemos nuestra propia conducta para limitar la difusión de información engañosa y exhortemos a nuestros líderes a trabajar en pos de la misma.

La rápida expansión de la digitalización y las plataformas en línea ha permitido que los contenidos engañosos se difundan más rápidamente y se disfracen de manera más eficaz. La organización sin fines de lucro First Draft News tiene lenguaje excelente que describe cómo se ve la manipulación de información hoy:

“El término ‘fake news’ no comienza a cubrir todo esto. La mayor parte de este contenido ni siquiera es falso; a menudo es genuino, usado fuera de contexto y armado por personas que saben que es más probable que se crean y se compartan las falsedades basadas en un núcleo de verdad. Y la mayor parte de esto no se puede describir como “noticias”. Son buenos rumores pasados de moda, son memes, son videos manipulados y “anuncios oscuros” hiperorientados y fotos antiguas que se vuelven a compartir como nuevas.

En First Draft, recomendamos el uso de los términos más apropiados para el tipo de contenido; ya sea propaganda, mentiras, conspiraciones, rumores, engaños, contenido híper partidista, falsedades o medios manipulados. También preferimos utilizar los términos desinformación, información errónea o información maliciosa. Colectivamente, lo llamamos desorden de la información “.

Definiciones

| Desorden de la información: término acuñado por First Draft News para abarcar el espectro de misinformación, mala información y desinformación Información errónea: contenido falso y la persona que comparte no se da cuenta de que es falso o engañoso. Información maliciosa: información genuina compartida con la intención de causar daño. Desinformación: contenido compartido que es intencionalmente falso y / o engañoso y diseñado para causar daño. Ciberseguridad social: la ciencia de caracterizar, comprender y pronosticar cambios mediados cibernéticamente en el comportamiento humano, los resultados sociales, culturales y políticos. |

Alguna desinformación es completamente falsa y inventada, como este artículo de “noticias” afirmando que el Papa Francisco tiene coronavirus. Como señala este usuario de Twitter, el dominio se registró hace varios años en China y cambió repentinamente unos días antes.

Fuente: https://twitter.com/cindyotis_/status/1233771696462684161

Se pueden utilizar los bots para amplificar los mensajes marginales a las audiencias principales. Trolls rusos, bots sofisticados y “contaminadores de contenido” tuitean sobre vacunas y mensajes antivacunas como este a tasas significativamente más altas que los usuarios medios. Se estima que el 25% de los tuits de negación climática son propagados por los bots.

Un ejemplo particular de preocupación se trata de servicios rusos de inteligencia que utilizaban publicidad pagada durante las elecciones estadounidenses de 2016 y que enviaron a diferentes audiencias diferentes mensajes dirigidos. Si bien los gobiernos nacionales han utilizado durante mucho tiempo información errónea contra los enemigos, las redes sociales han cambiado fundamentalmente el ámbito y el alcance de estas campañas. El objetivo de los anuncios era ampliar las divisiones existentes en EE. UU., no simplemente promover mensajes contradictorios. El uso notable de lenguaje e imágenes inflamatorios y los nombres deliberadamente engañosos de las páginas de Facebook contribuyeron a la confusión — no hay nada que demuestra que estos anuncios hayan sido pagados por actores extranjeros.

Fuente: https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2017/business/russian-ads-facebo…

Comprensión del desorden de la información y las campañas de desinformación

Aproximadamente 4 de cada 10 estadounidenses dicen que a menudo se encuentran con noticias e información inventadas. Aunque el campo emergente de ciberseguridad social apenas está comenzando a medir cómo el desorden de la información afecta a las personas y la sociedad, tenemos una comprensión bastante buena de cómo se difunde la información manipulada.

Las campañas de desinformación se diseñan deliberadamente para difundir información falsa o engañosa. Sin embargo, es posible que el mensaje de la campaña en sí no sea el objetivo real. Una táctica común es primero identificar dos grupos a favor y en contra de un tema divisivo (el aborto, las vacunas, el cambio climático y la ideología política son ejemplos excelentes). Una campaña de desinformación eficaz se infiltraría en ambos lados, respaldando a los líderes del grupo y ayudando a desarrollar cualidades de una caja de resonancia en el grupo. En cajas de resonancia, los miembros del grupo marginan la información externa, transmiten información interna extremadamente rápido y tomar decisiones basadas en la emoción y “lo que todos saben”. Las campañas utilizan esta toma de decisiones basada en la emoción para incitar sentimientos como consternación o entusiasmo en ambos grupos, y luego enfrentan a los dos lados el uno con el otro. En última instancia, ambos sufren de una falta de comunicación entre temas y pierden aún más la confianza en “el otro”, en resumen, agrandando la división entre los dos lados.

Los investigadores están extremadamente preocupados porque las campañas de desinformación socavan los procesos democráticos fomentando la duda y desestabilizando los puntos comunes que las sociedades democráticas requieren. “[Es como] escuchando estática a través de los audífonos,” dice la Dra. Kate Starbird, profesora de la Universidad de Washington. “Está diseñado para abrumar nuestra capacidad de dar sentido a la información, para hacernos pensar que la respuesta más saludable es desconectarnos. Y es posible que tengamos dificultades viendo el problema cuando el contenido se alinea con nuestras identidades políticas.”

¿Quién crea y difunde información errónea?

La mayor parte de la información errónea que se ve es creada y difundida por siete tipos de actores: bromistas, estafadores, entidades impulsadas por intereses, teóricos de la conspiración, “personas involucradas”, celebridades o sus amigos y familiares. Hemos discutido la función de muchos de estos actores en otras partes de nuestro recurso de desinformación, pero aún no hemos abordado el papel de las personas con información privilegiada o “personas involucradas”, los teóricos de la conspiración y las celebridades como fuentes y difusores de información errónea.

Las personas involucradas, o aquellos que revelan información confidencial al público en general, a menudo se consideran figuras controvertidas. Sin embargo, un número creciente de “personas involucradas” no son verdaderas personas involucradas en absoluto: son simplemente individuos que reclaman credenciales falsas para dar crédito a su desinformación. Al comienzo de la pandemia y el confinamiento del COVID-19, los mensajes sobre las “curas” del coronavirus y las medidas preventivas reclamaron la autoridad de los expertos taiwaneses, los médicos japoneses y la junta del hospital de Stanford. Sin embargo, estos mensajes, que casi siempre eran falsos y a veces dañosos, no habían sido escritos ni respaldados por ninguno de los expertos enumerados. Al evaluar la confiabilidad de una persona potencialmente con información privilegiada, sospeche de credenciales vagas o información transmitida por “un amigo de un amigo”. Un denunciante genuino que ha compartido sus preocupaciones a través de los canales adecuados bien podría tener derecho al anonimato. Alguien que comparte reclamos a través de las redes sociales o el correo electrónico probablemente no lo esté.

Existe una gran posibilidad de que crea o encuentre credibilidad en al menos una teoría de la conspiración: más del 60% de los estadounidenses lo cree. Las teorías de la conspiración, de alguna manera contradictoria, ofrecen racionalidad en un mundo arbitrario e impredecible. Según John Cook, experto en desinformación del Centro de Comunicación sobre el Cambio Climático de la Universidad George Mason, “le da a la gente más sentido de control imaginar que, en lugar de que sucedan cosas al azar, existen estos grupos y agencias en la sombra que lo controlan. La aleatoriedad es muy incómoda para la gente “. Las teorías de la conspiración florecen a raíz de eventos cataclísmicos como una pandemia o un bombardeo y pueden ser casi imposibles de refutar. Dado que la mayoría de las conspiraciones incluyen la creencia en algún tipo de encubrimiento, las refutaciones o bromas sobre una teoría de la conspiración simplemente proporcionan más “evidencia” de que se está perpetuando un encubrimiento.

Las audiencias que consumen principalmente los medios convencionales ven muchas más historias falsas de información privilegiada y teorías de conspiración de las que se imaginan. Mientras los medios convencionales en sí siguen siendo altamente confiables, los algoritmos en línea que favorecen el contenido con alta participación en lugar de contenido con alta veracidad facilitan la transmisión de información errónea a estas audiencias a través de plataformas ampliamente utilizadas como Facebook, Twitter y YouTube. Las personas notorias, como las celebridades, son facilitadores claves para este tipo de difusión de información errónea. Al examinar cómo viaja la información errónea de COVID-19, por ejemplo, las publicaciones de información errónea de celebridades, políticos y otras figuras públicas prominentes representaron casi el 70% de la participación total en las redes sociales, aunque esas publicaciones representaron solo el 20% del contenido total de información errónea de COVID-19. Este tipo de participación utiliza la falacia lógica de apelar a la autoridad: la alta visibilidad de un individuo en las redes sociales no significa que tenga la experiencia para evaluar si todo lo que ve y comparte es cierto.

Sobre política y teorías de la conspiración

Cada vez más, las teorías de la conspiración de la izquierda alternativa y de la derecha alternativa se discuten seriamente en los círculos políticos como conceptos legítimos. Esta tendencia es particularmente preocupante dado la posible influencia de esta información errónea en los legisladores y la legislación que autorizan. Sin embargo, las conspiraciones de extrema izquierda y extrema derecha no se promueven de la misma manera: es más probable que las conspiraciones de extrema derecha se difundan a través de redes coordinadas en los canales principales, dándoles un mayor alcance y una mayor legitimidad percibida. Independientemente de la orientación política, debemos esforzarnos por evaluar cuidadosamente toda la información que afectará nuestros sistemas de gobierno y evitar el uso de especulaciones sin fundamento para determinar la política pública.

Sobre las elecciones

Las elecciones y la política siempre han supuesto desinformación y manipulación. A menudo, la capacidad de un político para utilizar y contrarrestar eficazmente estas estrategias es una señal de competencia política. Considere a Odiseo, “el hombre de giros y vueltas”, cuya astucia e ilusionismo fueron elogiados por hombres y dioses en las epopeyas griegas La Ilíada y La Odisea. Sin embargo, las sociedades democráticas dependen de las elecciones justas y libres para garantizar que el gobierno derive su autoridad de la voluntad del pueblo. Las campañas de desinformación dirigidas a los votantes socavan la capacidad de un país para celebrar elecciones libres y justas. Hay varias tácticas utilizadas para este objetivo.

La “microtargeting” de las comunidades es particularmente preocupante: ¿cómo puede una elección ser justa si una comunidad recibe mensajes engañosos y altamente focalizados que la instan a votar a favor o en contra de un candidato? O peor aún, ¿qué sucede cuando los mensajes dirigidos anuncian la hora, el lugar o el método incorrecto para votar a un grupo en particular, como los “Texto para votar por Hillary” anuncios? Incluso la amenaza de tales acciones socava la confianza en los sistemas democráticos.

Ahora sabemos que durante los últimos años las campañas digitales internacionales dirigidas en los EE. UU. y en todo el mundo han trabajado para difundir contenido intencionalmente erróneo, socavar la fe en los procedimientos electorales y ampliar las divisiones existentes en varios países. Sin embargo, incluso las organizaciones nacionales de EE. UU. utilizan cada vez más estas mismas técnicas de desinformación para ganancias de elecciones a corto plazo o por motivos políticos. En última instancia, la desinformación electoral impulsada por todos los actores debilita el sistema democrático.

La Iglesia Episcopal reconoce que el proceso de votación y participación política es un acto de mayordomía cristiana y que dichos procesos deben ser imparciales, seguros y justos (vea resoluciones EC022020.16 y 2018-D096). Dado que la información errónea amenaza este proceso, la Iglesia Episcopal pide a todos sus miembros que estén atentos al interactuar con la información en línea y les anima a que verifiquen los datos y identifiquen la fuente para limitar la difusión de información errónea. Además, instamos a los episcopales a responsabilizar a los funcionarios del gobierno por limitar la difusión de información falsa y diseñada para causar daño.

¿Qué puedo hacer?

La desinformación a menudo se propaga más rápido que las noticias reales y llega a un público más amplio. También es cada vez más difícil de identificar. El primer paso para abordar la desinformación es el reconocimiento: todos contribuimos al problema, y todos debemos asumir la responsabilidad para detenerlo. Mientras la desinformación siga siendo un problema para que “el otro” resuelva —Generación Z, Boomers, Facebook, Millennials, suegros— va a persistir.

No captaremos toda la información errónea que nos llega. Pero antes de compartir ese tuit o contarle a un amigo sobre ese titular sorprendente que vio, hágase tres preguntas:

- ¿De dónde es? Busque la fuente y tenga cuidado con los sitios web falsos de imitación.

- ¿Qué falta? ¿Coinciden el titular y el artículo? ¿Están hablando de eso otras organizaciones de noticias?

- ¿Cómo se siente? Si un titular o artículo genera una emoción intensa como miedo, ira o reivindicación, esté atento. Esa es una táctica común de alguien que intenta manipularle, no de alguien que intenta difundir noticias de confianza.

Otras cosas a considerar:

- Aprenda en quién confiar. Una consecuencia desafortunada de la vigilancia de la desinformación puede ser la censura a través del ruido. Si la vigilancia nos lleva a desconfiar de todos los titulares, los que promueven la desinformación están triunfando. Esto significa que es menos probable que recibamos información precisa e informativa. Aprender quién produce en general información precisa es tan importante como examinar cuidadosamente las fuentes desconocidas.

- El género importa. No es solo artículos satíricos de la publicación “el Onion” que se comparten como una “noticia”. Tenga en cuenta las diferencias en la presentación, el protocolo de verificación de hechos y los estándares de responsabilidad entre la investigación revisada por pares, los artículos de noticias verificados por los hechos, los artículos de opinión y los programas de entrevistas y las diversas formas de sátira, propaganda y chismes.

- Una forma eficaz de acabar con las campañas de desinformación es etiquetarlas. Si bien es posible que no desee participar en los debates de hilos de comentarios en las redes sociales, considere hacer un comentario o enviar un mensaje privado a amigos y familiares cuando compartan una publicación que sospecha que es falsa o engañosa. ¡Y sea receptivo a los mismos comentarios de los demás!

- Comunicarse con los funcionarios electos que la protección contra las campañas de desinformación es importante para usted.

- Considere pedir a sus miembros del Congreso que apoyen la seguridad electoral. Los proyectos de ley debatidos en el 116 ° Congreso de los EE. UU. incluyen el “DETER Act” S. 1060, “Honest Ads Act” S.1356/H.R.2592, y “SHIELD Act” H.R. 4617.

- Desarrollar una comprensión matizada de la relación entre la libertad de expresión y la desinformación. Considere: ¿Ofrece (o debería) la Constitución a los anuncios comerciales o políticos pagados las mismas protecciones de libertad de expresión que a las personas? ¿La libertad de expresión también incluye la libertad de recibir información? Si es así, ¿la desinformación amenaza ese derecho? ¿Quién (si es que hay alguien) debería ser responsable de rastrear / etiquetar información falsa? ¿Debería haber límites para el anonimato web o los requisitos de divulgación del autor?

Recursos adicionales

Si desea obtener más información sobre el desorden de la información, aquí tiene algunas recomendaciones:

- Comprender el desorden de la información – un examen completo pero muy legible del panorama moderno del desorden de la información

- Periodismo, noticias falsas y desinformación: Módulo 2 (UNESCO)

- FactChat: una herriamienta bilingüe por La Red Internacional de Verificación de Datos (ICFN) junto con Univision y Telemundo para combatir la desinformación en WhatsApp

- La caja de herramientas de hechos completos – Cómo detectar rápidamente posible información errónea antes de compartirla. También incluye enlaces a numerosos sitios web de verificación de datos.

- Bot Sentinel – Recurso que le permite ver qué temas son tendencia en las cuentas de Twitter de bots sospechosos por día / hora. También puede poner cualquier nombre de usuario de Twitter y obtener una puntuación sobre si parece una cuenta de bot sospechosa.

- Interferencia extranjera y las elecciones de 2020

- ¡Cuestionarios para ver qué tan bien detecta la información errónea!

- Artículos de noticias

- Publicaciones en redes sociales

Resoluciones de la Convención General y el Consejo Ejecutivo

- 2022-D063 – Desinformación y elecciones

- EXC062016.07 – Apoyo a la reforma financiera de campañas

- Resolución 2018-D096 – Urgir la promoción de la buena gobernanza y la participación justa

Sobre el censo de EE. UU. 2020

Cada 10 años, el gobierno de los Estados Unidos realiza un esfuerzo masivo para contar a todas las personas que viven en el país. Este recuento es de suma importancia: determina la representación en el Congreso, se utiliza para asignar fondos federales para la próxima década y proporciona información valiosa para los funcionarios comunitarios estatales y locales, los proveedores de servicios y las empresas privadas. La información errónea sobre el censo se difunde fácilmente y es increíblemente dañoso. Las comunidades donde la información errónea del censo es más desenfrenada son a menudo aquellas con subgrupos “difíciles de contar” que tienen más que ganar con los recuentos de población precisos.

Los objetivos de la información errónea del censo a menudo incluyen:

- Privacidad de datos y estafas financieras. Lo que necesita saber: La Oficina del Censo nunca le pedirá su número de Seguro Social, número de tarjeta de crédito o cuenta bancaria, ni una donación financiera.

- Encuestadores en persona. Lo que necesita saber: durante la primavera y el verano del censo de 2020, los encuestadores en persona visitarán los hogares para dar el seguimiento a las personas que aún no han respondido. Todos los trabajadores llevan una tarjeta de identificación con su fotografía, una marca de agua del Departamento de Comercio de EE. UU. y la fecha de vencimiento. Si tiene preguntas sobre su identidad, puede llamar al + 1-844-330-2020 para hablar con un representante de la Oficina del Censo.

- Garantías de privacidad y protección de datos. Lo que necesita saber: Según el Título 13 del Código de los EE. UU., los datos del censo SOLAMENTE pueden usarse con fines estadísticos. La Oficina del Censo no puede divulgar ninguna información identificable sobre usted, su hogar o su negocio, ni siquiera a las agencias del orden público.

Puede aprender más sobre la información errónea del censo y cómo combatirla en el sitio web oficial del censo de EE. UU. Además, no se pierda la serie del censo y la caja de herramientas de participación del censo de la Oficina de Relaciones Gubernamentales.

Sobre COVID-19

La incertidumbre y el miedo que rodean al COVID-19 crean un entorno perfecto para que la información errónea sobre la enfermedad se difunda rápidamente y ampliamente, tanto que la Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS) advirtió que combatir esta enfermedad también requerirá combatir un “infodemic.” Los temas de información errónea incluyen los orígenes de la enfermedad, cómo se propaga, cómo tratarla, las respuestas de las autoridades y las acciones de las comunidades. Individuos en los EE. UU. y en el extranjero ya han muerto por seguir consejos falsos sobre el tratamiento y los métodos de prevención del coronavirus.

En medio de esta infodemia, la Oficina de Relaciones Gubernamentales insta a todos a obtener y compartir información sobre la enfermedad del coronavirus directamente del Organización Mundial de la Salud, los Centros para el Control y la Prevención de Enfermedades, Universidad John Hopkins o sus proveedores de atención médica locales. Sabemos que la orientación de estas agencias puede fluctuar y a veces cambiar por completo. Sin embargo, comprenda que esto se debe a que estas agencias están haciendo su diligencia debida para brindar transparencia al público sobre esta crisis de salud y para ajustar sus recomendaciones a medida que surgen nuevas investigaciones científicas.

¿Qué pasa con las mascarillas?

Nuestros trabajadores de la salud que interactúan directamente con muchos pacientes de COVID-19 tienen algunos de los riesgos más altos de contraer esta enfermedad y son uno de los grupos más importantes para mantenerse saludables y en el trabajo. Debido a esto, el suministro limitado de N95 y mascarillas quirúrgicas se está dirigiendo hacia este grupo. Otras cubiertas faciales, incluidas las hechas en casa, no son muy buenas para proteger a las personas del COVID-19 y otras enfermedades infecciosas, por lo que los CDC no recomendaron originalmente que las usara el público en general. Sin embargo, estas mascarillas de bajo grado pueden reducir la propagación de COVID-19 de las personas que ya están infectadas. A medida que salieron los datos de que muchos casos de COVID-19 estaban siendo transmitidos por personas que no sabían que tenían la enfermedad, los CDC cambiaron su recomendación de mascarilla para alentar al público en general a usar una. El uso de una mascarilla de tela no evitará directamente que se enferme, pero si usted y todos los que lo rodean usan una, es mucho menos probable que se contagien la enfermedad entre sí.

¿Qué más deberíamos estar haciendo?

Los consejos de salud actuales son rutinarios pero muy importantes de seguir. Las mejores prácticas recomendadas por los CDC para todos en la actualidad incluyen:

- Lávese las manos con frecuencia

- Evite el contacto cercano

- Cúbrase la boca y la nariz con una mascarilla de tela cuando esté cerca de otras personas

- Cúbrase la nariz y la boca al toser y estornudar

- Limpiar y desinfectar

Para las personas infectadas con COVID-19, sabemos que existen varias sugerencias para aliviar los síntomas en el hogar. Esté atento a los tratamientos con efectos secundarios potencialmente peligrosos y recuerde dar el seguimiento de cualquier medicamento que tome, incluidos los suplementos naturales o herbales. Si su condición empeora, esta información ayudará a su médico a saber cuál es la mejor forma de tratarlo.

Mientras luchamos contra esta pandemia global, asegurémonos de que nuestras acciones están limitando la propagación de esta enfermedad, no aumentando la propagación de información errónea.

Sobre los peligros de la desinformación patrocinada por el gobierno

Las campañas de desinformación patrocinadas por el gobierno tienen el poder de dañar a la sociedad. Por lo general, las personas tienen algo que decir sobre la cantidad de redes sociales que consumen y de cuál organización quieren recibir noticias. Pero dado que los gobiernos son nuestros órganos legislativos con el poder y la autoridad para hacer cumplir esas leyes, todos debemos prestar atención a las campañas de información patrocinadas por el gobierno. Si estas campañas se utilizan para difundir información falsa o engañosa a los ciudadanos, especialmente si el engaño es intencional, el daño social comienza a acumularse. Así es como:

1. Erosión de la confianza.

La desinformación respaldada por el gobierno puede erosionar la confianza entre las ramas del gobierno, entre un gobierno y sus ciudadanos, y en la esfera internacional. Estadounidenses, por ejemplo, tienen menos confianza en el gobierno federal que en el gobierno estatal o local y también creen que es menos probable que el gobierno federal proporcione información justa y precisa. Esta falta de confianza hace que sea mucho más difícil coordinar esfuerzos como la ayuda en casos de desastre y las recomendaciones de atención médica, al tiempo que abre la puerta a otros actores con menos supervisión y responsabilidad para convertirse en proveedores primarios de información. En sociedades democráticas que dependen mucho más explícitamente de un nivel de confianza entre los funcionarios electos y los electores, la erosión de la confianza puede representar una amenaza a largo plazo para los sistemas de gobierno estables.

2. Falta de responsabilidad.

Ninguna autoridad quiere ser responsable de una iniciativa fallida, una pobre respuesta a un desastre u otras crisis en las que se percibe que el gobierno ha manejado mal la situación. Las campañas de desinformación pueden permitir a los gobiernos echar la culpa a otros chivos expiatorios o negar la existencia de un problema por completo y evitar acciones productivas para abordar el problema.

3. Fomenta la difusión de más información errónea.

Las campañas de desinformación a menudo producen beneficios a corto plazo, aunque las repercusiones a largo plazo pueden finalmente lastimar el gobierno que patrocina la campaña. Una vez que un gobierno comienza a depender de la desinformación, se vuelve atractivo para otros intereses nacionales y extranjeros encabezar sus propias campañas, ya sea a través de una racionalización de “ellos-lo-hacen-por-qué-no-debería-yo” o por el deseo de seguir siendo competitivos en la esfera de influencia de la información.

Sobre las vacunas

Las vacunas son uno de los mayores logros médicos de la historia: extraordinariamente seguras, increíblemente eficaces y una vez superado el desarrollo inicial, a menudo resultan económicas de producir. Las vacunas han salvado millones de vidas y protegen a un número aún mayor de personas de condiciones médicas debilitantes de toda la vida que pueden resultar de un caso grave de una enfermedad infecciosa. En el mundo actual de COVID-19, los expertos predicen que es probable que la vida no vuelva a la “normalidad” hasta que se desarrolle una vacuna y pueda distribuirse ampliamente.

Un movimiento contra las vacunas ha persistido casi desde la invención de las vacunas. Tras la introducción de la vacuna contra la viruela en el siglo XIX, movimientos antivacunas se extendió por Gran Bretaña y los Estados Unidos alimentada por el escepticismo de la ciencia, la desaprobación y el miedo al método de la vacuna y una objeción a las infracciones de la libertad personal cuando la legislación ordenó las vacunas. Más recientemente, un estudio fraudulento publicado en 1998 pretendía demostrar un vínculo entre la vacuna contra el sarampión, las paperas y la rubéola (MMR) y el autismo. Este documento, y otros similares, han contribuido a que miles de padres elijan no vacunar a sus hijos, a pesar de que las investigaciones muestran que los datos del estudio fueron falsificado y el autor principal no reveló un conflicto de intereses financiero significativo.

La información errónea sobre las vacunas es increíblemente omnipresente y fácil de encontrar en la cultura rica en medios de hoy. Las plataformas brindan a ex científicos y médicos desacreditados, como el autor principal del estudio fraudulento de la vacuna MMR, una forma de difundir sus puntos de vista a una amplia audiencia con muy poca supervisión o responsabilidad.

Es cierto que las vacunas, como cualquier medicamento, a veces provocan efectos secundarios inesperados. Sin embargo, los efectos secundarios graves de las vacunas estándar son increíblemente raros y es mucho menos probable que ocurran en comparación a los efectos secundarios graves que se pueden desarrollar al contraer una enfermedad infecciosa. Los médicos limitan aún más la probabilidad de efectos secundarios graves al no vacunar al pequeño porcentaje de la población que tiene un mayor riesgo de experimentar una reacción negativa.

Elegir no vacunar por una razón no médica no solo pone en riesgo a la persona en cuestión: también crea un entorno para que las enfermedades infecciosas se propaguen a quienes, por razones de salud, no pueden vacunarse y, a menudo, corren el riesgo de desarrollar síntomas más graves de una enfermedad. Debido a que rechazar las vacunas conlleva importantes riesgos para la salud pública de muchos miembros de la comunidad, los tribunales de los EE. UU. generalmente han ratificado la autoridad de los estados para exigir las vacunas, señalando que el derecho de un individuo a la libertad personal o religiosa no reemplaza la responsabilidad del estado de proteger al público. Aproximadamente 1,5 millones de personas mueren cada año por enfermedades prevenibles mediante vacunación. En un esfuerzo por proteger a todos sus miembros y a nuestros vecinos, la Iglesia Episcopal no reconoce exenciones teológicas o religiosas para las vacunas y requiere vacunas para todos los participantes y el personal en los eventos episcopales (excepto aquellos con una exención médica). Obtenga más información sobre cómo involucrar a las comunidades religiosas en la inmunización de The World Faiths Development Dialogue.

Si tiene preguntas sobre las vacunas:

- Hable con su proveedor de atención médica primaria. Pueden explicar los posibles efectos secundarios de la vacuna, los posibles efectos secundarios de contraer una enfermedad y los riesgos relativos de cada uno. Su proveedor de atención médica primaria también debe estar informado de cualquier condición médica preexistente que usted o sus hijos tengan.

- Realice investigaciones en línea de fuentes confiables, como los Centros para el Control de Enfermedades. Hay mucha información falsa, engañosa o incompleta sobre las vacunas. Asegúrese de que la comunidad médica haya examinado minuciosamente cualquier información que utilice.

Sobre el cambio climático

La desinformación no es la única razón para la negación del cambio climático en los EE. UU., pero definitivamente es un factor importante que contribuye. Según la científica climática Dra. Katherine Hayhoe, las 6 etapas de la negación climática se pueden resumir de la siguiente manera: “No es real. No somos nosotros. No está tan mal. Es demasiado caro de arreglar. Ajá, aquí hay una gran solución (que en realidad no hace nada). Y … ¡oh no! Ahora es demasiado tarde. Realmente deberías habernos advertido antes “.

En 1856, la científica aficionada Eunice Foote publicó un artículo en el American Journal of Science sobre su descubrimiento de las propiedades de captura del calor del dióxido de carbono y teorizó que una atmósfera con una mayor concentración de CO2 daría como resultado una Tierra más cálida. Un siglo y medio después, la ciencia se ha vuelto más clara: el cambio climático es real, los humanos lo están causando y las soluciones deben implementarse lo más rápido posible. Sin embargo, el creciente consenso científico fue acompañado por el creciente cuerpo de desinformación climática financiado por la industria de los combustibles fósiles y la filantropía privada. Deberíamos tener conversaciones sobre las soluciones al cambio climático y cuáles acuerdos mutuos son necesarios para implementarlos. En cambio, continuamos debatiendo lo que ya es consenso científico y nos esforzamos por corregir los errores que propaga la información errónea.

La afiliación política – no el conocimiento científico – es un predictor clave de la creencia de un individuo en el cambio climático en los EE. UU. Esta división partidista, alimentada por la información errónea, ha estancado la legislación bipartidista para abordar el cambio climático durante más de 20 años. Hasta el día de hoy, se han tomado muy pocas acciones a nivel federal para disminuir la huella de carbono de los Estados Unidos. Incluso dentro de la comunidad ambiental, la desinformación climática persiste: un documental ambiental lanzado alrededor del Día de la Tierra 2020 recibió críticas mordaces por mezclar preguntas importantes sobre el sector de las energías renovables con una enorme cantidad de datos desactualizados, engañosos y falsos.

El cambio climático ya es una de las crisis más difíciles de nuestro tiempo que debemos abordar. No hagamos más difícil la implementación de soluciones utilizando información errónea para disfrazar el problema y arruinar los debates.

Para obtener más información sobre la ciencia del cambio climático:

Para obtener más información sobre las soluciones al cambio climático:

- Proyecto Drawdown

- Simulador de clima interactivo En-ROADS

- Recursos de cuidado de la creación de la Oficina de Relaciones Gubernamentales

- El Ministerio de Cuidado de la Creación de la Iglesia Episcopal

Una Reflexión sobre la Información Errónea, la Libertad de Expresión y la Democracia

En la fe cristiana, las palabras son poderosas. La palabra hablada de Dios en Génesis manda la existencia del universo, y Juan identifica a Jesús como esta palabra hablada al principio de su evangelio: “En el principio ya existía el Verbo, y el Verbo estaba con Dios, y el Verbo era Dios” (Juan 1:1).

Los fundadores de nuestro país también reconocieron el poder de las palabras y lo protegieron en la primera enmienda a la Constitución de los Estados Unidos: el gobierno “no promulgará ninguna ley” que restrinja “la libertad de expresión o de prensa; o el derecho de las personas a reunirse pacíficamente.” A lo largo de los años, los tribunales han mantenido en su mayoría (en Inglés) esta protección, incluso para las formas de expresión que a muchos estadounidenses les parecen ofensivas, como el material sexualmente explícito y el discurso de odio. Aunque el discurso, como cualquier herramienta, se puede usar con fines buenos o maliciosos, la ley de los Estados Unidos y los tribunales han dictado que, en casi todos los casos, la respuesta al discurso “malo” debe ser el discurso y el diálogo correctivos, no la censura.

Si bien la libertad de expresión es una herramienta increíblemente importante para proteger la democracia, también puede utilizarse como arma para socavarla. Salvo una pequeña categoría de expresión como difamación e información que pone en riesgo la vida de alguien, las protecciones de la libertad de expresión en los Estados Unidos no distinguen entre información verdadera y falsa: ambas están protegidas por la ley. En el panorama actual de los medios en línea, donde todos pueden ser editores, es posible que las campañas coordinadas promulguen la “censura a través del ruido” (en Inglés), oscureciendo la verdad a través del gran volumen y la propaganda de ideas falsas.

Recuerde: las palabras tienen poder. La mayoría de nosotros conoce el dicho: “No crea todo lo que ve en Internet”. Pero nuestro cerebro recuerda el contenido que vemos con mayor frecuencia (en Inglés) sin clasificarlo como “hecho” o “posible información errónea”. En un ecosistema de censura a través del ruido, un gran porcentaje de lo que vemos y escuchamos en el Internet, y por lo tanto recordamos, es información errónea. Algunos de nosotros podríamos clasificar con precisión esta información errónea como falsa. Algunos de nosotros podemos aceptarla incorrectamente como un hecho. Ninguno/a tiene la verdad real guardada en nuestra memoria: se logró la censura.

La democracia se basa en que los votantes sean informados y educados para seleccionar representantes que defenderán sus intereses. Ambas la censura directa y la censura a través del ruido amenazan la capacidad de los votantes (en Inglés) de estar informados sobre los candidatos y los temas. Por lo tanto, encontrar una manera de limitar la información errónea sin recurrir a la censura es fundamental para proteger la democracia.

El Papel y las Limitaciones de los Guardianes de la Media

Las plataformas en línea tienen poderes y protecciones únicos conferidos por la Sección 230 de la Ley de Decencia en las Comunicaciones (en Inglés) que no están en los manos de los guardianes de los medios tradicionales. Los legisladores reconocieron en la década de 1990 que los usuarios terceros podían representar un desafío difícil para las plataformas de Internet. Considere un sitio web, desde Facebook hasta un pequeño bloguero, que quiera permitir que los visitantes publiquen comentarios. ¿Qué sucede si un visitante publica material sexualmente explícito o algo ilegal? ¿Es el sitio web responsable si moderan, o no moderan, este contenido?

La solución de los legisladores para este problema dio las plataformas de Internet dos cosas:

- Protección de responsabilidad por el contenido de terceros en su plataforma

- Capacidad para ejercer voluntariamente la discreción editorial de buena fe sobre el contenido de terceros, como eliminar una publicación con malas palabras. Esta discreción editorial también hace que sea perfectamente legal que la plataforma modere el contenido de una manera que promueva un punto de vista político, moral o social (en Inglés).